Hippocrates

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Human Scientists

| Hippokrates of Kos ( Greek: Ἱπποκράτης) |

|

|---|---|

|

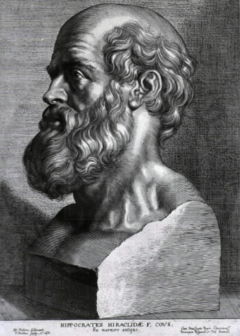

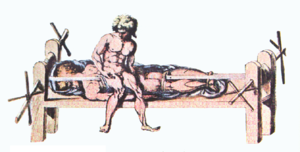

Engraving by Peter Paul Rubens, 1638, courtesy of the National Library of Medicine .

|

|

| Born | c. 460 BC |

| Died | c. 370 BC |

| Occupation | Physician |

Hippocrates of Cos II. or Hippokrates of Kos (c. 460 BC–c. 370 BC, Greek: Ἱπποκράτης) was an ancient Greek physician who lived in the Age of Pericles and is one of the most outstanding figures in the history of medicine. He is often referred to as " The Father of Medicine" for his lasting contributions to the field as the founder of the Hippocratic school of medicine which revolutionized medicine in ancient Greece, separating the field from the other disciplines (notably theurgy and philosophy) and making a profession of practicing medicine. The school summed up the medical knowledge of previous schools and defined moral codes and good habits for physicians.

The Hippocratic Corpus, or the collection of works commonly associated with Hippocrates, was the medium through which Hippocratic philosophy transmitted the above. It is largely responsible for Hippocrates's renown. The great detail and depth of the descriptions in its constituent works are still respected as is the Hippocratic Oath, the most famous work in it. The Corpus is not necessarily of Hippocrates's own hand, and there are many doubts as the the authenticity of the collection, the Oath included. As the Hippocratic Corpus is, however, the primary source for information concerning Hippocrates and the Hippocratic school of medicine, the achievements of all three are not generally separated.

Biography

Historians accept that Hippocrates actually existed, was born near the year 460 BC on the island of Kos and was a famous physician and teacher of medicine. All other biographical information is possibly apocryphal (See Legends). As no real biography was available until centuries after his death, those that are available today must be based on many years of oral tradition and are thus unreliable.

Soranus of Ephesus, also a mysterious figure, was Hippocrates's first biographer and is the source of most information, however unreliable, on Hippocrates's person. Soranus stated that Hippocrates's father, a physician, was Heraclides, and his mother, daughter of Phenaretis, was named Praxitela. He had two sons, Thessalus and Draco, and a son-in-law, Polybus. All three were his students, but Polybus was Hippocrates’ true successor according to Galen, a later physician, who also stated that Thessalus and Draco each had a son named Hippocrates. Other biographers, in addition to Soranus and Galen, were Suidas, John Tzetzes, and Aristotle.

Soranus said that Hippocrates was taught medicine by his father and grandfather, and other subjects by Democritus and Gorgias. Hippocrates could have been trained at the Asklepieion of Kos, and may have been a pupil of Herodicus of Selymbria: Plato, Hippocrates's only contemporary to mention him, describes him as an Asclepiad.

Hippocrates taught and practiced medicine throughout his long life, traveling significantly to do so. He went at least as far as Thessaly, Thrace, and the Sea of Marmara. He may have died in Larissa at the age of 83 or 90, though his death date is speculated with very little certainty; some sources state that he lived to be over 100 years old.

Hippocratic theory

Hippocrates is credited as the first physician to reject the divine origin and superstition of all sicknesses. He separated the discipline of medicine from philosophy and religions, believing and proffering that disease was not punishment of the gods but due to environmental factors, diet and living habits. Indeed, there is not a single mention of a mystical illness in the entirety of the Hippocratic Corpus. Hippocrates did not, however, hold entirely scientific beliefs; he held many pseudo-scientific convictions based on bad anatomy and physiology, such as Humorism.

Indeed, Greek medicine at the time of Hippocrates knew almost nothing of human anatomy and physiology because of the Greek taboo forbidding the dissection of animals. Ancient Greek schools of medicine were split (into the Knidian and Koan) on how to deal with this. The Knidian school of medicine focused on diagnosis, but, dependent upon faulty assumptions about the human body, failed to distinguish when one disease caused many possible series of symptoms.

The Hippocratic school or the Koan school, however, was more successful for its general diagnoses and passive treatments. The focus of Hippocratic medicine was on patient care and prognosis and not diagnosis. It could effectively treat many diseases, yet it allowed for a great development in clinical practice; it was more successful than the Knidian.

Hippocratic medicine and philosophy, for all of its advances, is far removed from modern medicine. Today, the physician focuses on specific diagnosis and specialized treatment, which are much more of the Knidian ideals. Following, Hippocratic methods have seen some serious criticism in the past two millennia. M. S. Houdart, a French doctor, called Hippocratic treatment a "meditation upon death." He said the purpose of the doctor was to cure the patient, not simply predict how he will die.

Humorism

Hippocrates, according to the Corpus, held that illness was the result of an imbalance in the body of the four humours, fluids which were naturally equal in proportion (pepsis). When the four humours, blood, black bile, yellow bile and phlegm, were unbalanced (dyscrasia, meaning "bad mixture"), a person became sick and would remain that way until the balance was somehow restored. Hippocratic therapy was directed towards this end, perhaps utilizing citrus, for instance, if there was thought to be an overabundance of phlegm.

Crisis

An important concept in Hippocratic medicine was that of a crisis, a point in the progression of disease at which either the illness would begin triumph and the patient would move to die, or the opposite, and natural processes would make the patient recover. After a crisis, a relapse might follow, and then another deciding crisis. By this doctrine, crises occur on critical days, which were supposed to be a fixed time after the contraction of a disease. If a crisis occurs on a day far from a critical day, a relapse may be expected. Galen believed that this idea originated with Hippocrates, though it is possible that it predated him.

Hippocratic therapy

Vis medicatrix naturae

Another important precept of Hippocratic doctrine was based on "the healing power of nature", or in Latin, vis medicatrix naturae. According to this doctrine, the body contains within itself the power to rebalance the four humours and heal itself (physis). Hippocratic therapy was focused on simply easing this natural process. To this end, Hippocrates believed "rest and immobilization [were] of capital importance". By these beliefs, he was reluctant to administer drugs and engage in specialized treatment that could be wrong; generalized therapy followed a generalized diagnosis.

Methods of treatment

Hippocratic medicine was humble and passive. Whenever possible it was very kind to the patient: sterile and gentle. For example, only clean water or wine were ever used on wounds, though "dry" treatment was preferable. There were, however, times when potent drugs were used.

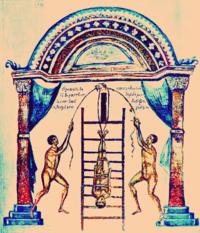

Hippocratic method was very successful in treating simple ailments such as broken bones which required traction to stretch the skeletal system and relieve pressure on the injured area. The Hippocratic bench, which preceded the torture device rack, and other devices were used to this end.

As was mentioned, one of the strengths of Hippocratic medicine was in its prognosis. At this time, medicinal therapy was quite immature, and often the best that physicians could do was evaluate an illness and induce the likely progression of it based upon data collected in detailed case histories.

Professionalism

Despite all of its advancements in medical theory, it was truly in discipline, strict professionalism and rigorous practice that Hippocratic medicine excelled.<specify>

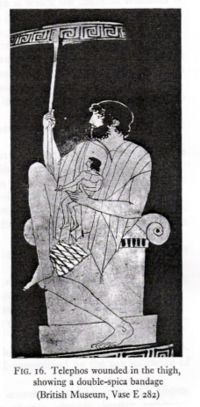

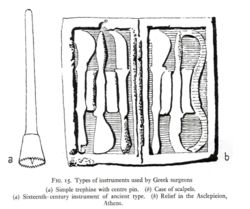

The Hippocratic work On the physician recommends that physicians be always be well-kempt, honest, calm, understanding and serious. Careful attention is paid to all aspects of a physicians's practice. Specifications for, "lighting, personnel, instruments, positioning of the patient, and techniques of bandaging and splinting" in the ancient operating room are described in detail. Even the length of a physician's fingernails is exactly specified.

The Hippocratic School is famous for its clinical doctrines of observation. These dictate that physicians record their findings and their medicinal methods in a very clear and objective manner, so that these records may be passed down and employed by other physicians. Hippocrates made careful, regular note of many symptoms including complexion, pulse, fever, pains, movement, and excretions. He might have even measured a patient's pulse when taking a case history to know if the patient lied.

Hippocrates extended clinical observations into family history and environment in accordance with this theory. "To him medicine owes the art of clinical inspection and observation" For this reason, he may termed only the "Father of Clinical Medicine".

Direct contributions to medicine

Hippocrates and his followers identified many diseases and medical conditions for the first time. He also began to categorize illnesses as acute, chronic, endemic and epidemic. Other medical terms that he introduced were, "exacerbation, relapse, resolution, crisis, paroxysm, peak, and convalescence."

Great contributions of Hippocrates may be found in his descriptions of the symptomology, physical findings, surgical treatment and prognosis of thoracic empyema, i.e. suppuration of the lining of the chest cavity.His teachings remain relevant to contemporary students of pulmonary medicine and surgery. Hippocrates was the first documented chest surgeon and his findings are still valid.

He is also given credit for the first description of clubbing of the fingers, an important diagnostic sign in chronic supperative lung disease, lung cancer and cyanotic heart disease. For this reason, clubbing is sometimes termed "Hippocratic fingers". Hippocrates was also the first one to diagnose Hippocratic face in Prognosis. Shakespeare famously aludes to this description when writing of the death of Falstaff in Act II, Scene iii. of Henry V.

The Hippocratic Corpus

The Hippocratic Corpus (Latin: Corpus Hippocratum) is a collection of around seventy early medical works from ancient Greece strongly associated with Hippocrates and his teachings. Of the volumes in the Corpus, none is proven to be of Hippocrates' hand itself, though some sources say otherwise.Instead, the works were probably produced by students and followers of his ( Ermerins numbers the authors at nineteenCite error 1; Invalid <ref> tag; name cannot be a simple integer, use a descriptive title, maybe centuries after he died. Because of the variety of subjects, writing styles and apparent date of construction, scholars believe it could not have been written by one person. But the corpus carries Hippocrates's name as it was attributed to him in antiquity and its teaching generally follow principles of his. It might be the remains of a library of Kos, or a collection compiled in the third century B.C. in Alexandria.

Content

The Hippocratic Corpus contains textbooks, lectures, research, notes and philosophical essays on various subjects in medicine, in no particular order. These works were written for different audiences, both specialists and laymen, and were sometimes written from opposing view points; significant contradictions can be found between works in the Corpus.

One significant portion of the corpus is made up of case-histories, of which there are forty-two. Of these, 60% (25) ended in the patient's death. Nearly all of the diseases described in the Corpus are endemic diseases: colds, consumption, pneumonia, etc.

Style

| "Life is short, [the] art long, opportunity fleeting, experiment treacherous, judgment difficult." —Aphorisms i.1. |

The writing style of the Corpus has been remarked upon for centuries, being described by some as, "clear, precise, and simple". It is often praised for its objectivity and concisesness, yet some have criticised it as being "grave and austere". Francis Adams, a translator of the Corpus, goes further and calls it sometimes “obscure”. Of course, not all of the Corpus is of this “laconic” style, though most of it is. It was Hippocratic practice to write in this style.

The whole corpus is written in Ionic Greek, though the island of Kos was in a region that spoke Doric Greek. This use of Ionic instead of the native Doric dialect is analogous to the practice of Renaissance scientists, using Latin instead of the vernacular for their treatises.

Printed editions

The entire Hippocratic Corpus was first printed as a unit in 1525. This edition was in Latin and was edited by Marcus Fabius Calvus in Rome. The first complete Greek edition followed the next year in Venice. An English translation was first published about 300 years later.

A significant edition was that of Émile Littré who spent twenty-two years (1839-1861) working diligently on the Hippocratic Corpus. This was scholarly, yet sometimes inaccurate and awkward. Another edition of note was that of Franz Z. Ermerins, published in Utrecht between 1859 and 1864. Beginning in 1967, an important modern edition by Jacques Jouanna and others began to appear (with Greek text, French translation, and commentary) in the Collection Budé. Other important bilingual annotated editions (with translation in German or French) continue to appear in the Corpus medicorum graecorum published by the Akademie-Verlag in Berlin.

The Oath

The most famous work in the Hippocratic corpus is the Hippocratic Oath, a landmark declaration of doctoral ethics historically taken at the beginning of a doctor's career. While the oath is rarely used in its original form today, it serves as a foundation for other, similar oaths and laws that define good medical practice and morals; derivatives of it are taken.

Legacy

For all of these above achievements, Hippocrates is widely considered the first great physician; however, for a long time, he was also the last. He is readily named the most important influence on medicine for over a thousand years, yet after him there was a dearth of medical advancement. Medical practitioners who followed him sometimes moved backwards. For instance, "after the Hippocratic period, the practice of taking clinical case-histories died out...", according to Fielding Garrison.

After Hippocrates, the next significant physician was Galen, a Greek who lived from 129 -200 AD. Galen perpetuated Hippocratic medicine, moving both forward and backward. In the Middle Ages, Arabs too, adopted Hippocratic methods. After the European Renaissance, Hippocratic methods were revived in Europe and even further expanded upon in the 1800s. Others that employed Hippocrates' rigorous clinical techniques were Sydenham, Heberden, Charcot and Osler. It has been said that these revivals make up "the whole history of internal medicine".

Image

According to Aristotle's testimony, Hippocrates was known as "the Great Hippocrates".So revered was Hippocrates at the time of his death that honey (from a beehive) on his grave was believed to have healing powers. But so revered was he, that, after him, no significant advancements were made for a long time. His teachings were largely taken as too great to be improved upon.

Concerning his disposition, Hippocrates was first portrayed as a, "kind, dignified, old 'country doctor'" and later as, "stern and forbidding". He is certainly considered wise and of very great intellect. He is seen as very practical, and Francis Adams (translator) describes him as "strictly the physician of experience and common sense".

His image as the wise, old doctor is reinforced by the busts of him, which all wear large beards. The image is probably close to the truth, though: the physicians of the time wore their hair in the style of Jove and Asclepius. Accordingly, the busts of Hippocrates that we have could be only altered versions of portraits of these deities. As is demonstrated by his mythical busts, Hippocrates and the beliefs that he embodied are considered medical ideals. "He is, above all, the exemplar of that flexible, critical, well-poised attitude of mind, ever on the lookout for sources of error, which is the very essence of the scientific spirit."(Garrison) "His figure... stands for all time as that of the ideal physician”(Singer and Underwood), inspiring the medical profession since his death.

Legends

Some stories of Hippocrates's life are likely to be untrue because they are considered inconsistent with other historical evidence. Even during his life, Hippocrates's renown was great, and stories of miraculous cures arose. For example, Hippocrates was supposed to have aided in the healing of Athenians during the Plague of Athens by lighting great fires as "disinfectants".There is a story of Hippocrates curing Perdiccas, a Macedonian king of " love sickness". Neither of these accounts are corroborated by any historians and is thus unlikely to have ever occurred.

One more probable legend concerns how Hippocrates rejected a formal request to visit the court of Artaxerxes, the King of Persia. The validity of this is accepted by ancient sources, denied by some modern ones and is thus under contention. In another tale, Democritus was supposed to be mad because he laughed at everything, and so he was sent to Hippocrates to be cured. Hippocrates diagnosed him as having a merely happy disposition. Democritus has since been called "the laughing philosopher".

Of course, not all stories of Hippocrates were postive. Indeed, in one, Hippocrates did his traveling only after he set fire to a healing temple in Greece; he fled from his crime. Soranus, the source of this story, names the temple as the one of Knidos. Tzetzes writes, however, that it was his own Temple of Cos that was burned; that he did it to maintain a monopoly of medical knowledge. This account is very much in conflict with traditional estimations of Hippocrates's personality.

Genealogy

With this figure of legend, comes a legendary genealogy, which traces Hippocrates’ heritage directly to Asclepius. It has also been said that in his mother's ancestry lies Hercules. The ahnentafel of Hippocrates II. is, according to Tzetzes’s Chiliades:

1. Hippocrates II. “The Father of Medicine”

2. Heraclides

4. Hippocrates I.

8. Gnosidicus

16. Nebrus

32. Sostratus III.

64. Theodorus II.

128. Sostratus, II.

256. Thedorus

512. Cleomyttades

1024. Crisamis

2048. Dardanus

4096. Sostatus

8192. Hippolochus

16384. Podalirius

32768. Asclepius

Namesakes

Ancient

- Hippocratic bench — a device which uses tension to aid in setting bones

- Hippocratic face — the change produced in the countenance by death, or long sickness, excessive evacuations, excessive hunger, and the like

- Hippocratic fingers — a deformity of the fingers and fingernails

- Hypocras — a drink whose invention is attributed to Hippocrates

- Hippocratic succussion — the internal splashing noise of hydropneumothorax or pyopneumothorax

Modern

- Hippocratic Museum

- The Hippocrates Project — A program of the New York University Medical Centre to enhance education through use of technology

- Project Hippocrates — "HIgh PerfOrmance Computing for Robot-AssisTEd Surgery"

- Digital Hippocrates — "a collection of Ancient Medical texts"

- Digital Hippocrates System — an anonymous, on-line, medical reference source directed at educating adolescents

- Hippocrates Project — A tissue engineering project