Henry V of England

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: British History 1500 and before (including Roman Britain); Monarchs of Great Britain

| Henry V | ||

|---|---|---|

| By the Grace of God, King of England, Heir and Regent of the Kingdom of France and Lord of Ireland |

||

|

||

| Reign | 21 March 1413 - 31 August 1422 | |

| Coronation | 1413 | |

| Born | 16 September 1387 | |

| Monmouth, Wales | ||

| Died | August 31, 1422 (aged 34) | |

| Bois de Vincennes, France | ||

| Buried | Westminster Abbey | |

| Predecessor | Henry IV | |

| Successor | Henry VI | |

| Consort | Catherine of Valois ( 1401- 1437) | |

| Issue | Henry VI ( 1421- 1471) | |

| Royal House | Lancaster | |

| Father | Henry IV ( 1367- 1413) | |

| Mother | Mary de Bohun (c. 1369- 1394) | |

Henry V of England ( 16 September 1387 – 31 August 1422) was one of the great warrior kings of the Middle Ages. He was born at Monmouth, Wales, on 9 August 1386 or 16 September 1387, and he reigned as King of England from 1413 to 1422.

Henry was son of Henry of Bolingbroke, later Henry IV, and Mary de Bohun, who died before Bolingbroke became king.

At the time of his birth during the reign of Richard II, Henry was fairly far removed from the throne, preceded by the King and another preceding collateral line of heirs. The precise date and even year of his birth are therefore not definitely recorded. By the time Henry died, he had not only consolidated power as the King of England but had also effectively accomplished what generations of his ancestors had failed to achieve through decades of war: unification of the crowns of England and France in a single person. In 2002 he was ranked 72nd in the 100 Greatest Britons poll.

Early accomplishments

Upon the exile of Henry's father in 1398, Richard II took the boy into his own charge and treated him kindly. In 1399 the Lancastrian usurpation brought Henry's father to the throne and Henry into prominence as heir to the Kingdom of England. He was created Duke of Lancaster on 10 November 1399, the third person to hold the title that year.

From October 1400 the administration was conducted in his name; less than three years later Henry was in actual command of the English forces and fought against Harry Hotspur at Shrewsbury. It was there, in 1403, that the sixteen-year-old prince was almost killed by an arrow which became lodged in his face. An ordinary soldier would have been left to die from such a wound, but Henry had the benefit of the best possible care, and, over a period of several days after the incident, the royal physician crafted a special tool to extract the tip of the arrow without doing further damage. The operation was successful, and probably gave the prince permanent scars which would have served as a testimony to his experience in battle.

Role in government and conflict with Henry IV

The Welsh revolt of Owain Glyndŵr absorbed Henry's energies until 1408. Then, as a result of the King's ill-health, Henry began to take a wider share in politics. From January 1410, helped by his uncles Henry and Thomas Beaufort — legitimised sons of John of Gaunt — he had practical control of the government.

Both in foreign and domestic policy he differed from the King, who in November 1411 discharged the Prince from the council. The quarrel of father and son was political only, though it is probable that the Beauforts had discussed the abdication of Henry IV, and their opponents certainly endeavoured to defame the prince. It may be to that political enmity that the tradition of Henry's riotous youth, immortalised by Shakespeare, is partly due. Henry's record of involvement in war and politics, even in his youth, disproves this tradition. The most famous incident, his quarrel with the chief justice, has no contemporary authority and was first related by Sir Thomas Elyot in 1531.

| English Royalty |

|---|

| House of Lancaster |

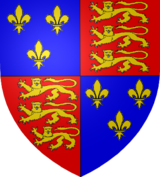

Armorial of Plantagenet |

| Henry V |

| Henry VI |

The story of Falstaff originated partly in Henry's early friendship with Sir John Oldcastle. That friendship, and the prince's political opposition to Thomas Arundel, Archbishop of Canterbury, perhaps encouraged Lollard hopes. If so, their disappointment may account for the statements of ecclesiastical writers, like Thomas Walsingham, that Henry on becoming king was changed suddenly into a new man.

Accession to the throne

After his father Henry IV died on 20 March 1413, Henry V succeeded him on 21 March 1413 and was crowned on 9 April 1413.

Domestic policy

Henry tackled all of the domestic policies together, and gradually built on them a wider policy. From the first, he made it clear that he would rule England as the head of a united nation, and that past differences were to be forgotten. The late king Richard II of England was honourably reinterred; the young Mortimer was taken into favour; the heirs of those who had suffered in the last reign were restored gradually to their titles and estates. Henry used his personal influence in vain, and the gravest domestic danger was Lollard discontent. But the king's firmness nipped the movement in the bud (January 1414), and made his own position as ruler secure.

With the exception of the Southampton Plot in favour of Mortimer, involving Henry Scrope, 3rd Baron Scrope of Masham and Richard, Earl of Cambridge (grandfather of the future King Edward IV of England) in July 1415, the rest of his reign was free from serious trouble at home.

Foreign affairs

Henry could now turn his attention to foreign affairs. A writer of the next generation was the first to allege that Henry was encouraged by ecclesiastical statesmen to enter into the French war as a means of diverting attention from home troubles. This story seems to have no foundation. Old commercial disputes and the support which the French had lent to Owain Glyndŵr were used as an excuse for war, whilst the disordered state of France afforded no security for peace. The French king, Charles VI, was prone to mental illness, and his eldest son an unpromising prospect.

Campaigns in France

Henry may have regarded the assertion of his own claims as part of his kingly duty, but in any case a permanent settlement of the national quarrel was essential to the success of his world policy.

- 1415 campaign

Henry sailed for France on 11 August 1415 where his forces besieged the fortress at Harfleur, capturing it on 22 September. Afterwards, Henry was obliged to march with his army across the French countryside with the intention to reach Calais. On the plains near the village of Agincourt, he turned to give battle to a pursuing French army. Despite his men-at-arms exhausted and outnumbered, Henry led his men into battle, miraculously defeating the French. With its brilliant conclusion at Agincourt on the 25 October 1415, this was only the first step.

- Diplomacy and command of the sea

The command of the sea was secured by driving the Genoese allies of the French out of the Channel.( His flagship, Grace Dieu – 1420) A successful diplomacy detached the emperor Sigismund from France, and by the Treaty of Canterbury paved the way to end the schism in the Church.

- 1417 campaign

So, with these two allies gone, and after two years of patient preparation since Agincourt, in 1417 the war was renewed on a larger scale. Lower Normandy was quickly conquered, Rouen cut off from Paris and besieged. The French were paralysed by the disputes of Burgundians and Armagnacs. Henry skilfully played them off one against the other, without relaxing his warlike energy. In January 1419 Rouen fell. By August the English were outside the walls of Paris. The intrigues of the French parties culminated in the assassination of John of Burgundy by the Dauphin's partisans at Montereau ( 10 September 1419). Philip, the new duke, and the French court threw themselves into Henry's arms. After six months' negotiation Henry was by the Treaty of Troyes recognised as heir and regent of France (see English Kings of France), and on 2 June 1420 married Catherine of Valois the king's daughter. From June to July his army besieged and took the castle at Montereau, and from that same month to November, he besieged and captured Melun, returning to England shortly thereafter.

- 1421 campaign

On 10 June 1421, Henry sailed back to France for what would now have been his last military campaign. From July to August, Henry's forces besieged and captured Dreux, thus relieving allied forces at Chartres. That October, his forces lay siege to Meaux, capturing it on 2 May 1422. Henry V died suddenly on 31 August 1422 at Bois de Vincennes near Paris, apparently from dysentery which he contracted during the siege of Meaux. He was 34 years old. Before his death, Henry V named his brother John, Duke of Bedford regent of France in the name of his son Henry VI, then only a few months old. Henry VI did not live to be crowned King of France himself, though ironically Charles VI died only two months later. Following his death, Catherine would secretly marry or have an affair with a Welsh courtier, Owen Tudor, and they would be the grandmother and grandfather of King Henry VII of England.

In literature

Henry V is the subject of the eponymous play by William Shakespeare, which largely concentrates on his campaigns in France. He is also a main character in Henry IV, Part 1 and Henry IV, Part 2, where Shakespeare dramatises him as a wanton youth.