Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: North American History

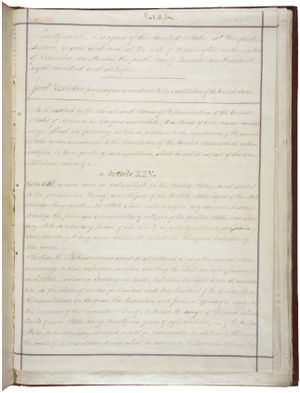

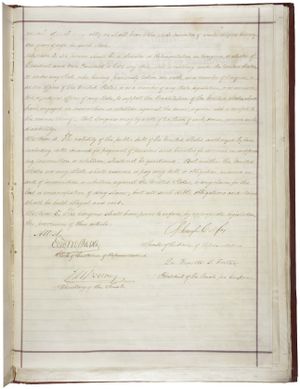

The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution is one of the post-Civil War amendments and it includes the Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses. It was proposed on June 13, 1866, and ratified on July 9, 1868.

The amendment provides a broad definition of national citizenship, overturning a central holding of the Dred Scott case. It requires the states to provide equal protection under the law to all persons (not only to citizens) within their jurisdictions.

Current Supreme Court Justice David Souter has called this amendment "the most significant structural provision adopted since the original Framing". ( McCreary County v. ACLU of Kentucky ( 2005)), although the true significance of the Amendment was not realized until the 1950s and 1960s, when it was interpreted to prohibit racial segregation in public schools and other facilities in Brown v. Board of Education.

Citizenship and civil rights

The first section formally defines citizenship and requires the states to provide civil rights.

Section 1. All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

This represented Congress's reversal of that portion of the Dred Scott v. Sandford decision that declared that African Americans were not and could not become citizens of the United States or enjoy any of the privileges and immunities of citizenship. The Civil Rights Act of 1866 had already granted U.S. citizenship to all people born in the United States; the framers of the Fourteenth Amendment enshrined this principle in the Constitution in order to stop the Supreme Court from ruling it unconstitutional for want of congressional authority to pass such a law, or from a future Congress altering it by a bare majority vote.

Citizenship and the children of legal and illegal immigrants

The provisions in Section 1 have been interpreted to the effect that children born on United States soil, with very few exceptions, are U.S. citizens. This type of guarantee—legally termed jus soli, or "right of the territory"— does not exist in most of Western Europe or the Middle East, although it is part of English common law and is common in the Americas.

The phrase and subject to the jurisdiction thereof indicates that there are some exceptions to the universal rule that birth on U.S. soil automatically grants citizenship. Two Supreme Court precedents were set by the cases of Elk v. Wilkins and United States v. Wong Kim Ark . Elk v. Wilkins established that Indian tribes represented independent political powers with no allegiance to the United States, and that their peoples were under a special jurisidiction of the United States. Children born to these Indian tribes therefore did not qualify for automatic citizenship under the Fourteenth Amendment. Indian tribes that paid taxes were exempt from this ruling; their peoples were already citizens by an earlier Act of Congress.

In Wong Kim Ark the Supreme Court held that under the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, a man born within the United States to foreigners (in that case, Chinese citizens) who were lawfully residing in the United States and who were not employed in a diplomatic or other official capacity by a foreign power, was a citizen of the United States.

Under these two rulings, the following persons born in the United States are not "subject to the jurisdiction [of the United States]", and thus do not qualify for automatic citizenship under the Fourteenth Amendment:

- Children born to foreign diplomats;

- Children born to enemy forces in hostile occupation of the United States;

- Children born to Native Americans who are members of tribes not taxed (these were later given full citizenship by the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924).

The following persons born in the United States are explicitly citizens:

- Children born to US citizens;

- Children born to aliens who are lawfully inside the United States (resident or visitor), with the intention of amicably interacting with its people and obeying its laws.

The Court in Wong Kim Ark did not explicitly decide whether U.S.-born children of illegal immigrants are "subject to the jurisdiction of the United States" (it was not necessary to answer this question since Wong Kim Ark's parents were legally present in the United States at the time of his birth). However, the Supreme Court's later ruling in Plyler v. Doe 457 U.S. 202 stated that illegal immigrants are "within the jurisdiction" of the states in which they reside, and added in a footnote that "no plausible distinction with respect to Fourteenth Amendment "jurisdiction" can be drawn between resident aliens whose entry into the United States was lawful, and resident aliens whose entry was unlawful."

This implies that the U.S.-born children of illegal immigrants qualify for citizenship under the Fourteenth Amendment.

Some legislators, reacting to illegal immigration, have proposed that this be changed, either through legislation or a constitutional amendment. The proposed changes are usually one of the following:

- The child should have at least one parent who is a U.S. citizen.

- The child should have at least one parent who is a U.S. citizen or permanent resident

- The child should have at least one parent who is lawfully present in the United States.

For example, Representative Nathan Deal, Republican of Georgia, introduced legislation in 2005 to that would provide that U.S.-born children would be "subject to the jurisdiction of the United States" (and therefore entitled to automatic citizenship under the Fourteenth Amendment) only if at least one parent were a U.S. citizen or permanent resident. .

Similarly, Representative Ron Paul of Texas has introduced a constitutional amendment that would deny automatic citizenship to U.S.-born children unless at least one parent is a citizen or permanent resident .

Neither of these measures has come to a vote.

Loss of citizenship

The Fourteenth Amendment does not provide any procedure for loss of United States citizenship. Indeed the Amendment, taken absolutely literally, would seem to imply that loss of U.S. citizenship is impossible for anyone born or naturalized in the United States. Under the Supreme Court precedent of Afroyim v. Rusk , loss of U.S. citizenship is possible only under the following circumstances:

- Fraud in the naturalization process. Technically this is not loss of citizenship, but rather a voiding of the purported naturalization and a declaration that the immigrant never was a U.S. citizen.

- Voluntary relinquishment of citizenship. This may be accomplished either through renunciation procedures specially established by the State Department or through other actions which demonstrate an intention to give up U.S. citizenship. Such actions include, under the laws and policies in operation as of 2006 :

- Treason against the United States.

- Voluntary service in a foreign army engaged in hostilities against the United States

- Accepting employment under foreign government if one is a national of the government or if one is required to make an oath of allegiance, if one intends to relinquish US nationality

Civil rights

Congress also passed the Fourteenth Amendment in response to the Black Codes that southern states had passed in the wake of the Thirteenth Amendment, which ended slavery in the United States. Those laws attempted to return freed slaves to something like their former condition by, among other things, restricting their movement and by preventing them from suing or testifying in court.

Early on, the Supreme Court limited the reach of the Amendment by holding in the Slaughterhouse Cases (1871) that the "privileges and immunities" clause was limited to "privileges and immunities" granted to citizens by the federal government. The Supreme Court held in the Civil Rights Cases that the Amendment was limited to "state action" and thus did not authorize Congress to outlaw racial discrimination on the part of private individuals or organizations. Neither of these decisions has been overturned and in fact have been specifically reaffirmed several times.

In the decades following the enactment of the Fourteenth Amendment, the Supreme Court overturned laws barring blacks from juries ( Strauder v. West Virginia) or discriminating against Chinese-Americans in the regulation of laundry businesses ( Yick Wo v. Hopkins), under the aegis of the Equal Protection Clause.

In Plessy v. Ferguson, the Supreme Court held that the states could impose segregation so long as they provided equivalent facilities—the genesis of the "separate but equal" doctrine. The popular understanding of what was encompassed under "civil rights" was much more restricted during the time of the Fourteenth Amendment's ratification than the present understanding, involving such things as equal treatment in criminal and civil court, in sentencing, and in availability of civil services if they apply. On this scheme, political rights were first guaranteed not with the Fourteenth Amendment but with the Fifteenth Amendment and its right to vote. Social rights first explicitly appeared with Loving v. Virginia (1967), which declared anti- miscegenation laws to be unconstitutional.

Many maintain that the Fourteenth Amendment was designed to encompass a broad anti-discrimination principle, or at least to declare personal rights broader than the restricted early conception of "civil rights". On this view, Plessy v. Ferguson sapped the equal protection clause of its original meaning in restricting its application to this degree. The Court went even further in restricting it in Berea College v. Kentucky, holding that the states could force private actors to discriminate by prohibiting an integrated college from admitting both black and white students. By the early twentieth century, the Equal Protection Clause had been eclipsed to the point that Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. dismissed it as "the usual last resort of constitutional arguments."

The Court held to the "separate but equal" doctrine for more than fifty years, despite numerous cases in which the Court itself had found that the segregated facilities provided by the states were almost never equal until the case Brown v. Board of Education happened. Brown met with a campaign of resistance from white Southerners, and for decades the federal courts attempted to enforce Brown's mandate against continual attempts at circumvention. This resulted in the controversial forced busing decrees handed down by federal courts in many parts of the nation, including major Northern cities like Detroit ( Milliken v. Bradley) and Boston.

In the half century since Brown, the Court has extended the reach of the Equal Protection Clause to other historically disadvantaged groups, such as women, aliens, and illegitimate children, although applying a somewhat less stringent test than it has applied to governmental discrimination on the basis of race.

For many years, beginning in the 1880s, the Court interpreted the Fourteenth Amendment's Due Process Clause as providing substantive protection to corporate interests. The Court held that the Fourteenth Amendment protected "freedom of contract", or the right of employees and employers to bargain for wages without great interference from the state. Thus, the Court struck down a law decreeing maximum hours for workers in a bakery in Lochner v. New York (1905), and struck down a minimum wage law in 1923's Adkins v. Children's Hospital. The Court did uphold some economic regulation, however, including state prohibition laws ( Mugler v. Kansas), laws declaring maximum hours for mine workers (Holden v. Hardy), laws declaring maximum hours for female workers ( Muller v. Oregon), as well as federal laws regulating narcotics (United States v. Doremus) and President Wilson's intervention in a railroad strike (Wilson v. New).

The Court overruled Lochner, Adkins, and other precedents protecting "liberty of contract" in 1937's West Coast Hotel v. Parrish, decided in the midst of the New Deal, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt threatened to " pack the court" to preserve his programs from being declared unconstitutional by the Court. However, it is important to note that as popular as Roosevelt was, his court packing plan failed miserably because it was seen as fundamentally changing the blueprint of the government. Also, we must note Footnote 4 of the Carolene Products case, in which the Supreme Court already noted the change in their stance, and their desire or at least felt obligation to inflate the balloon of equality rights liberalism opposed to freedom of contract liberalism.

Yet while the Supreme Court has emphatically rejected the substantive due process precedents that allowed it to overturn states' economic regulations, in the past forty years it has recognized a number of "fundamental rights" of individuals, such as privacy and some parental rights, which the states can regulate only under narrowly defined circumstances. The Court has also greatly expanded the reach of procedural due process, requiring some sort of hearing before the government may terminate civil service employees, expel a student from public school or cut off a welfare recipient's benefits.

Through the doctrine of Incorporation, the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment has also brought about the application of nearly all of the rights explicitly enumerated in the Bill of Rights to the states. Prior to the adoption of this Amendment, the Bill of Rights acted only as a restraint on federal, not state, governments, and a state's relations with its citizens and those of other states was legally restrained only by that state's constitution and laws and those provisions of the Constitution that limited the powers of the states. While many states modeled their constitutions and laws after the federal government's, those state constitutions did not necessarily include provisions comparable to the Bill of Rights.

The Fourteenth Amendment not only empowered the federal courts to intervene in this area to enforce the guarantee of due process and the equal protection of the laws, but to import the substantive rights of free speech, freedom of religion, protection from unreasonable searches and cruel and unusual punishment and other limitations on governmental power. At the present, the Supreme Court has held that the due process clause incorporates all of the substantive protections of the First, Fourth, Sixth, and Eighth Amendments and all of the Fifth Amendment other than the requirement that any criminal prosecution must follow a grand jury indictment, but none of the provisions of the Seventh Amendment relating to civil trials.

Though the framers of the Fourteenth Amendment did not believe the Amendment would create new political rights (leading to the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment, protecting the right of blacks to vote on equal terms with whites), the Supreme Court, since 1962's Baker v. Carr and 1964's Reynolds v. Sims, has interpreted the Equal Protection Clause as requiring the states to apportion their congressional delegations and legislatures on a "one-man, one-vote" basis. Attempts to extend this principle to attempts at gerrymandering have thus far stalled.

Apportionment of representatives

The second section establishes rules for the apportioning of representatives in Congress to states, essentially counting all residents for apportionment and reducing apportionment if a state wrongfully denies a person's right to vote.

Section 2. Representatives shall be apportioned among the several States according to their respective numbers, counting the whole number of persons in each State, excluding Indians not taxed. But when the right to vote at any election for the choice of electors for President and Vice President of the United States, Representatives in Congress, the Executive and Judicial officers of a State, or the members of the Legislature thereof, is denied to any of the male inhabitants of such State, being twenty-one years of age, and citizens of the United States, or in any way abridged, except for participation in rebellion, or other crime, the basis of representation therein shall be reduced in the proportion which the number of such male citizens shall bear to the whole number of male citizens twenty-one years of age in such State.

This section overrode the provisions of the Constitution that counted slaves as three-fifths of a person for purposes of allotting seats in the House of Representatives and the Electoral College.

Participants in rebellion

Section 3. No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. But Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.

The third section prevents the election of any person to the Congress or Electoral College who had held any of certain offices and then engaged in insurrection, rebellion, or treason. A two-thirds vote by Congress can override this limitation, however. This disqualification could not have been enacted as a statute, because it would have been an ex post facto punishment. In 1978, two-thirds votes of both Houses of Congress were obtained posthumously removing the service ban from Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis.

Validity of public debt

Section 4. The validity of the public debt of the United States, authorized by law, including debts incurred for payment of pensions and bounties for services in suppressing insurrection or rebellion, shall not be questioned. But neither the United States nor any State shall assume or pay any debt or obligation incurred in aid of insurrection or rebellion against the United States, or any claim for the loss or emancipation of any slave; but all such debts, obligations and claims shall be held illegal and void.

The fourth section confirmed that the United States would not pay "damages" for the loss of slaves, nor debts that had been incurred by the Confederacy — for example, several English and French banks had loaned money to the South during the war. In spite of the Amendment, Confederate bonds were traded on money markets for many years, albeit at a great discount from par, on the hope that the U.S. would eventually stand behind them. Similarly, Czarist bonds were traded for many years in the forlorn hope that the USSR would honour them.

Power of enforcement

Section 5. The Congress shall have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.

The fifth section empowers Congress to enforce the amendment "by appropriate legislation." Although in Katzenbach v. Morgan ( 1966) the Warren Court construed this section broadly, the Rehnquist Court tended to construe it narrowly, as in City of Boerne v. Flores ( 1997) or Board of Trustees of the University of Alabama v. Garrett ( 2001). But see Tennessee v. Lane and Nevada Department of Human Resources v. Hibbs.

Proposal and ratification

The Congress proposed the Fourteenth Amendment on June 13, 1866. There being thirty-seven states in the Union at that time, the ratification (per Article Five of the Constitution) of twenty-eight would bring this Amendment into operation. By July 9, 1868, twenty-eight states had ratified the Amendment:

- Connecticut ( June 25, 1866)

- New Hampshire ( July 6, 1866)

- Tennessee ( July 19, 1866)

- New Jersey ( September 11, 1866)

- Oregon ( September 19, 1866)

- Vermont ( October 30, 1866)

- Ohio ( January 4, 1867)

- New York ( January 10, 1867)

- Kansas ( January 11, 1867)

- Illinois ( January 15, 1867)

- West Virginia ( January 16, 1867)

- Michigan ( January 16, 1867)

- Minnesota ( January 16, 1867)

- Maine ( January 19, 1867)

- Nevada ( January 22, 1867)

- Indiana ( January 23, 1867)

- Missouri ( January 25, 1867)

- Rhode Island ( February 7, 1867)

- Wisconsin, ( February 7, 1867)

- Pennsylvania ( February 12, 1867)

- Massachusetts ( March 20, 1867)

- Nebraska ( June 15, 1867)

- Iowa ( March 16, 1868)

- Arkansas ( April 6, 1868)

- Florida ( June 9, 1868)

- North Carolina, ( July 4, 1868, after having rejected it on December 14, 1866)

- Louisiana ( July 9, 1868, after having rejected it on February 6, 1867)

- South Carolina ( July 9, 1868, after having rejected it on December 20, 1866)

However, Ohio passed a resolution that purported to withdraw their ratification on January 15, 1868. The New Jersey legislature also tried to rescind their ratification on February 20, 1868. The New Jersey governor had vetoed their withdrawal on March 5, and the legislature overrode the veto on March 24. Accordingly, on July 20, 1868, Secretary of State William Seward certified that the amendment had become part of the constitution if the rescissions were ineffective. Congress responded on the following day, declaring that the amendment was part of the constitution and ordering Seward to promulgate the Amendment.

Meanwhile, two additional states had ratified the amendment:

- Alabama ( July 13, 1868, the date the ratification was "approved" by the governor)

- Georgia ( July 21, 1868, after having rejected it on November 9, 1866)

Thus, on July 28, Seward was able to certify unconditionally that the Amendment was part of the constitution without having to endorse Congress's assertion that the withdrawals were ineffective.

There were further, purely symbolic, ratifications and rescissions:

- Oregon (withdrew October 15, 1868)

- Virginia ( October 8, 1869, after having rejected it on January 9, 1867)

- Mississippi ( January 17, 1870)

- Texas ( February 18, 1870, after having rejected it on October 27, 1866)

- Delaware ( February 12, 1901, after having rejected it on February 7, 1867)

- Maryland (1959)

- California (1959)

- Kentucky (1976, after having rejected it on January 8, 1867)

Controversy over ratification

A number of individuals argue that the ratification of the 14th Amendment violated Article V of the Constitution. For instance, Bruce Ackerman argues that:

- The 14th Amendment was proposed by a rump Congress that did not include representatives and senators from most ex-Confederate states, and, had those congressmen been present, the Amendment would never have passed.

- Ex-Confederate states were counted for Article V purposes of ratification, but were not counted for Article I purposes of representation in Congress.

- The ratifications of the ex-Confederate states were not truly free, but were coerced. For instance, many ex-Confederate states had their readmittance to the Union conditioned on ratifying the 14th Amendment.

(See Amar, Akhil Reed. America's Constitution: A Biography. p. 364–365; See also Douglas H. Bryant, Unorthodox and Paradox: Revisiting the Ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment, Alabama Law Review, Winter 2002.)

In Dyett v. Turner, 439 P.2d 266 (Utah 1968), the Utah Supreme Court diverged from the habeas corpus issue in the case to express its resentment against recent decisions of the U.S. Supreme Court under the Fourteenth Amendment, and to attack the Amendment itself:

In order to have 27 states ratify the Fourteenth Amendment, it was necessary to count those states which had first rejected and then under the duress of military occupation had ratified, and then also to count those states which initially ratified but subsequently rejected the proposal. To leave such dishonest counting to a fractional part of Congress is dangerous in the extreme. What is to prevent any political party having control of both houses of Congress from refusing to seat the opposition and then without more passing a joint resolution to the effect that the Constitution is amended and that it is the duty of the Administrator of the General Services Administration to proclaim the adoption? Would the Supreme Court of the United States still say the problem was political and refuse to determine whether constitutional standards had been met? How can it be conceived in the minds of anyone that a combination of powerful states can by force of arms deny another state a right to have representation in Congress until it has ratified an amendment which its people oppose? The Fourteenth Amendment was adopted by means almost as bad as that suggested above.

Relevant court cases

|

|