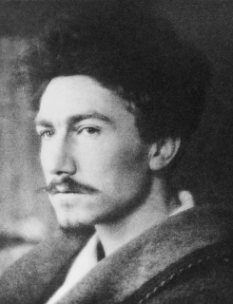

Ezra Pound

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Writers and critics

Ezra Weston Loomis Pound ( October 30, 1885 – November 1, 1972) was an American expatriate, poet, musician, and critic who, along with T. S. Eliot, was a major figure of the Modernist movement in early 20th century poetry. He was the driving force behind several Modernist movements, notably Imagism and Vorticism. The critic Hugh Kenner said on meeting Pound: "I suddenly knew that I was in the presence of the centre of modernism."

Early life and contemporaries

Pound was born in Hailey, Idaho, United States to Homer Loomis and Isabel Weston Pound. He studied for two years at the University of Pennsylvania and later received his B.A. from Hamilton College in 1905. During studies at Penn, he met and befriended William Carlos Williams and H.D. ( Hilda Doolittle), to whom he was engaged for a time. H.D. also became involved with a woman named Frances Gregg around this time. Shortly afterwards, H.D. and Gregg, along with Gregg's mother, went to Europe.

Afterward, Pound taught at Wabash College in Crawfordsville, Indiana for less than a year, and left as the result of a minor scandal. In 1908 he traveled to Europe, settling in London after spending several months in Venice.

The London Revolution

Pound's early poetry was inspired by his reading of the pre-Raphaelites and other 19th century poets and medieval Romance literature, as well as much neo-Romantic and occult/mystical philosophy. When he moved to London, under the influence of Ford Madox Ford and T. E. Hulme, he began to cast off overtly archaic poetic language and forms in an attempt to remake himself as a poet. He believed W. B. Yeats was the greatest living poet, and befriended him in England, eventually being employed as the Irish poet's secretary. He was also interested in Yeats's occult beliefs. During the war, Pound and Yeats lived together at Stone Cottage in Sussex, England, studying Japanese, especially Noh plays. They paid particular attention to the works of Ernest Fenollosa, an American professor in Japan, whose work on Chinese characters Pound developed into what he called the Ideogrammic Method. In 1914, Pound married Dorothy Shakespear, an artist, and the daughter of Olivia Shakespear, a novelist and former lover of W.B. Yeats.

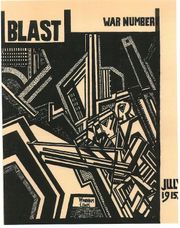

In the years before the First World War, Pound was largely responsible for the appearance of Imagism, and contributed the name to the movement known as Vorticism, which was led by Wyndham Lewis. These two movements, which helped bring to notice the work of poets and artists like James Joyce, Wyndham Lewis, William Carlos Williams, H.D., Richard Aldington, Marianne Moore, Rabindranath Tagore, Robert Frost, Rebecca West and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, can be seen as central events in the birth of English-language modernism. Pound also edited his friend Eliot's The Waste Land, the poem that was to force the new poetic sensibility into public attention.

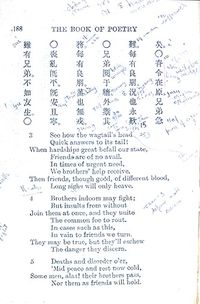

In 1915, Pound published Cathay, a small volume of poems that Pound described as “For the most part from the Chinese of Rihaku [Li Po], from the notes of the late Ernest Fenollosa, and the decipherings of the professors Mori and Ariga.". The volume includes works such as The River Merchant's Wife: A Letter and A Ballad of the Mulberry Road. Unlike previous American translators of Chinese poetry, who tended to work with strict metrical and stanzaic patterns, Pound offered readers free verse translations celebrated for their ease of diction and conversationality. Many critics consider the poems in Cathay to be the most successful realization of Pound's Imagist poetics. Whether or not the poems are valuable as translations continues to be a source of controversy. Neither Pound nor Fenollosa spoke or read Chinese proficiently, and Pound has been criticized for omitting or adding sections to his poems which have no basis in the original texts. Many critics argue, however, that the fidelity of Cathay to the original Chinese is beside the point. Hugh Kenner, in a chapter entitled "The Invention of China," contends that Cathay should be read primarily as a book about World War I, not as an attempt at accurately translating ancient Eastern poems. The real achievement of the book, Kenner argues, is in how it combines meditations on violence and friendship with an effort to "rethink the nature of an English poem" . These ostensible translations of ancient Eastern texts, Kenner argues, are actually experiments in English poetics and compelling elegies for a warring West.

The war shattered Pound's belief in modern western civilization and he abandoned London soon after, but not before he published Homage to Sextus Propertius ( 1919) and Hugh Selwyn Mauberley ( 1920). If these poems together form a farewell to Pound's London career, The Cantos, which he began in 1915, pointed his way forward.

Paris

In 1920, Pound moved to Paris where he moved among a circle of artists, musicians and writers who were revolutionising the whole world of modern art. He was friends with notable figures such as Marcel Duchamp, Tristan Tzara, Fernand Leger and others of the Dada and Surrealist movements. He continued working on The Cantos, writing the bulk of the "Malatesta Sequence" which introduced one of the major personas of the poem. The poem increasingly reflected his preoccupations with politics and economics. During this time, he also wrote critical prose, translations and composed two complete operas (with help from George Antheil) and several pieces for solo violin. In 1922 he met and became involved with Olga Rudge, a violinist. Together with Dorothy Shakespear, they formed an uneasy ménage à trois which was to last until the end of the poet's life.

Italy

On 10 October 1924, Pound left Paris permanently and moved to Rapallo, Italy. He and Dorothy stayed there briefly, moving on to Sicily, and then returning to settle in Rapallo in January 1925. In Italy he continued to be a creative catalyst. The young sculptor Heinz Henghes came to see Pound, arriving penniless. He was given lodging and marble to carve, and quickly learned to work in stone. The poet James Laughlin was also inspired at this time to start the publishing company New Directions which would become a vehicle for many new authors.

At this time Pound also organized an annual series of concerts in Rapallo where a wide range of classical and contemporary music was performed. In particular this musical activity contributed to the 20th century revival of interest in Vivaldi, who had been neglected since his death.

In Italy Pound became an enthusiastic supporter of Mussolini, and anti-Semitic sentiments begin to appear in his writings. He made his first trip back home for many years in 1939, on the eve of the Second World War, and considered moving back permanently, but in the end he chose to return to Italy.

Aside from his political sympathy with the Mussolini regime, Pound had personal reasons for staying. His elderly parents had retired to Italy to be with him, and were in poor health and would have difficulty making the trip back to America even under peacetime conditions. He also had an Italian-born daughter by his mistress Olga Rudge: Mary (or Maria) Rudge was a young woman in her late teens who had lived in Italy her whole life and who might have had difficulty relocating to America (even though she had American as well as Italian citizenship.)

Pound remained in Italy after the outbreak of the Second World War, which began more than two years before his native United States formally entered the war in December 1941. He became a leading Axis propagandist. He also continued to be involved in scholarly publishing, and he wrote many newspaper pieces. He disapproved of American involvement in the war and tried to use his political contacts in Washington D.C. to prevent it. He spoke on Italian radio and gave a series of talks on cultural matters. Inevitably, he touched on political matters, and his opposition to the war and his anti-Semitism were apparent on occasions. A transcript from one of his broadcasts reads: "The big Jew is so bound up with this Leihkapital that no one is able to unscramble that omelet. It would be better for you to retire to Darbyshire and defy New Jerusalem, better for you to retire to Gloucester and find one spot that is England than to go on fighting for Jewry and ignoring the process....You let in the Jew and the Jew rotted your empire, and you yourselves out-jewed the Jew....And the big Jew has rotted EVERY nation he has wormed into" (March 15, 1942).

It is not clear if anyone in the United States ever actually heard his radio broadcasts, since Italian radio's shortwave transmitters were weak and unreliable. It is clear, however, that his writings for Italian newspapers (as well as a number of books and pamphlets) did have some influence in Italy.

In July 1943, the southern half of Italy was overrun by Allied forces. At the Allies' behest, King Victor Emmanuel III dismissed Mussolini as premier of the Kingdom of Italy. Mussolini escaped to the north, where he declared himself the President of the new Salo Republic. Pound played a significant role in cultural and propaganda activities in the new republic, which lasted till the spring of 1945.

On May 2, 1945, he was arrested by Italian partisans, and taken (according to Hugh Kenner) "to their HQ in Chiavari, where he was soon released as possessing no interest." The next day, he turned himself in to U.S. forces. He was incarcerated in a United States Army detention camp outside Pisa, spending twenty-five days in an open cage before being given a tent. Here he appears to have suffered a nervous breakdown. He also drafted the Pisan Cantos in the camp. This section of the work in progress marks a shift in Pound's work, being a meditation on his own and Europe's ruin and on his place in the natural world. The Pisan Cantos won the first Bollingen Prize from the Library of Congress in 1948.

St. Elizabeths

After the war, Pound was brought back to the United States to face charges of treason. The charges covered only his activities during the time when the Kingdom of Italy was officially at war with the United States, i.e., the time before the Allies captured Rome and Mussolini fled to the North. Pound was not prosecuted for his activities on behalf of Mussolini's Saló Republic (evidently because the Republic's existence was never formally recognized by the United States). He was found unfit to face trial because of insanity and sent to St. Elizabeths Hospital in Washington, D.C., where he remained for 12 years from 1946 to 1958. His insanity plea is still a matter of some controversy, since in retrospect his activities and his writings during the war years do not appear to be those of a clinically insane person. The insanity plea was part of a plea bargain designed to save his life, since treason is potentially a capital offense. As it turned out, there were a number of other American Axis collaborators who stood trial after the war without being sentenced to death. Pound's controversial insanity plea is mirrored by the fate of Norwegian author and collaborator Knut Hamsun, who was similarly dubbed insane by embarrassed authorities despite evidence (in the form of subsequent published material) to the contrary.

Following his release, Pound was asked his opinions on his home country. He famously quipped: "America is a lunatic asylum." Subsequently he returned to Italy, where he remained until his death in 1972. Pound was conceited and flamboyant, not to say obsessive, which in psychiatric terms became "grandiosity of ideas and beliefs."

By contrast, E. Fuller Torrey believed that Pound was coddled by Winfred Overholser, the superintendent of St. Elizabeths. According to Torrey, Overholser admired Pound's poetry and allowed him to live in a private room at the hospital, where he wrote three books, received visits from literary celebrities and enjoyed conjugal relations with his wife and several mistresses. However, the reliability of Torrey’s allegations has been questioned. Other scholars have presented Overholser as behaving solely in a humane way to his famous patient, without allowing him special privileges. At St. Elizabeths, Pound was surrounded by poets and other admirers and continued working on The Cantos as well as translating the Confucian classics.

One of Pound's most frequent visitors was the then-chairman of the States' Rights Democratic Party, with whom Pound used to discuss strategy and tactics on how best to rally public support for the preservation of racial segregation in the American South.

Pound was also befriended there by Hugh Kenner, whose The Poetry of Ezra Pound (1951) was highly influential in causing a re-assessment of Pound's poetry. Other scholars began to edit the Pound Newsletter, which eventually led to the publication of the first guide to The Cantos, Annotated Index to the Cantos of Ezra Pound (1957). Pound was most happy in his relations with fellow-poets, like Elizabeth Bishop, who recorded her response to Pound’s tragic situation in the poem " Visits to St. Elizabeths," and Robert Lowell, who visited and corresponded extensively with Pound. Another visitor who is believed to have inspired the love-poetry in Cantos XC-XCV was the artist Sheri Martinelli. Both William Carlos Williams and Louis Zukosfsky were among Pound's visitors, as was Guy Davenport, who subsequently wrote his Harvard dissertation on Pound's poetry (published as Cities on Hills in 1983). Pound was finally released after a concerted campaign by many of his fellow poets and artists, particularly Robert Frost and Archibald MacLeish. He was still considered incurably insane, but not dangerous to others.

Return to Italy and Death

On his release, Pound returned to Italy where he continued writing, but his old certainties had deserted him. Although he continued working on The Cantos, he seemed to view them as an artistic failure. Allen Ginsberg, in an interview with Michael Reck, stated that Pound seemed to regret many of his past actions, and that he regretted that his work was tainted with "that stupid, suburban prejudice of anti-Semitism" , although contemporaneous letters published in recent years indicate that he was still unrepentently anti-Semitic. Pound died in Venice in 1972.

Musical Quality of Pound's Poetry

Pound's The Cantos, one of the 20th century's most important literary works, is a poem that contains music and bears a title that could be translated as The Songs --though it never is. Pound's ear was tuned to the motz el sons of troubadour poetry where, as musicologist John Stevens has noted, "melody and poem existed in a state of the closest symbiosis, obeying the same laws and striving in their different media for the same sound-ideal - armonia."

In his essays, Pound wrote of rhythm as "the hardest quality of a man's style to counterfeit." He challenged young poets to train their ear with translation work to learn how the choice of words and the movement of the words combined. But having translated texts from ten different languages into English, Pound found that translation did not always serve the poetry: "The grand bogies for young men who want really to learn strophe writing are Catullus and Francois Villon. I personally have been reduced to setting them to music as I cannot translate them." While he habitually wrote out verse rhythms as musical lines, Pound did not set his own poetry to music.

In 1919, when he was 34, Pound began charting his path as a novice composer, writing privately that he intended a revolt against the impressionistic music of Debussy. An autodidact, Pound described his working method as "improving a system by refraining from obedience to all its present 'laws'..." With only a few formal lessons in music composition, Pound produced a small body of work, including a setting of Dante's sestina, "Al poco giorno," for violin. His most important output is the pair of operas: Le Testament, a setting of Francois Villon's long poem of that name, written in 1461; and Cavalcanti, a setting of 11 poems by Guido Cavalcanti (c. 1250-1300). Pound began composing the Villon with the help of Agnes Bedford, London pianist and vocal coach. Though the work is notated in Bedford's hand, Pound scholar Robert Hughes has been able to determine that Pound was artistically responsible for the work's overall dramatic and acoustic design.

During the fecund Paris years of 1921-1924, Pound formed close friendships with the American pianist and composer George Antheil, and Antheil's touring partner, the American concert violinist Olga Rudge. Pound championed Antheil's music and asked his help in devising a system of micro-rhythms that would more accurately render the vitalistic speech rhythms of Villon's Old French for Le Testament. The resulting collaboration of 1923 used irregular meters that were considerably more elaborate than Stravinsky's benchmarks of the period, Le Sacre du Printemps (1913) and L'Histoire du Soldat (1918). For example, "Heaulmiere," one of the opera's key arias, at a tempo of quarter note = M.M. 88, moves from 2/8 to 25/32 to 3/8 to 2/4 meter (bars 25-28), creating for the performers ferocious difficulties in hearing the current bar of music and anticipating the upcoming bar. Rudge performed in the 1924 and 1926 Paris preview concerts of Le Testament, but insisted to Pound that the meter was impractical.

In Le Testament there is no predictability of manner; no comfort zone for singer or listener; no rests or breath marks. Though Pound stays within the hexatonic scale to evoke the feel of troubadour melodies, modern invention runs throughout, from the stream of unrelenting dissonance in the mother's prayer to the grand shape of the work's aesthetic arc over a period of almost an hour. The rhythm carries the emotion. The music admits the corporeal rhythms (the score calls for human bones to be used in the percussion part); scratches, hiccoughs, and counter-rhythms lurch against each other--an offense to courtly etiquette. With "melody against ground tone and forced against another melody," as Pound puts it, the work spawns a polyphony in polyrhythms that ignores traditional laws of harmony. It was a test of Pound's ideal of an "absolute" and "uncounterfeitable" rhythm conducted in the laboratory of someone obsessed with the relationship between words and music.

After hearing a concert performance of Le Testament in 1926, Virgil Thomson praised Pound's accomplishment. "The music was not quite a musician's music," he wrote, "though it may well be the finest poet's music since Thomas Campion. . . . Its sound has remained in my memory."

Robert Hughes has remarked that where Le Testament explores a Webernesque pointillistic orchestration and derives its vitality from complex rhythms, Cavalcanti (1931) thrives on extensions of melody. Based on the lyric love poetry of Guido Cavalcanti, the opera's numbers are characterized by a challenging bel canto, into which Pound incorporates a number of tongue-in-cheek references to Verdi and a musical motive that gestures to Stravinsky's neo-classicism. By this time the relationship with Antheil had considerably cooled, and Pound, in his gradual acquisition of technical self-sufficiency, was free to emulate certain aspects of Stravinsky. Cavalcanti demands attention to its varying cadences, to a recurring leitmotif, and to a symbolic use of octaves. The play of octaves creates a surrealist straining against the limits of established compositional laws, of history and fate, of physiology, of reason, and especially against the limits of a love born of desire. The audience is asked to strain to hear a political cipher hidden within the music.

Pound's statement, "Rhythm is a FORM cut into TIME," distinguishes his 20th century medievalism from Antheil's SPACE/TIME theory of modern music, which sought pure abstraction. Antheil's system of time organization is inherently biased for complex, asymmetric, and fast tempi; it thrives on innovation and surprise. Pound's more open system allows for any sequence of pitches; it can accommodate older styles of music with their symmetry, repetition, and more uniform tempi, as well as newer methods, such as the asymmetrical micro-metrical divisions of rhythm created for Le Testament.

Pound's iconoclastic music can be compared to that of his contemporary, Charles Ives. Both subjected melody to sophisticated techniques of juxtaposition and layering, Pound shaping melody with literary textures and Ives with harmonic and contrapuntal textures. Each experimented with the combination of different genres placed into a single complex work. Ives selected from among hymns, folk tunes, ballads and minstrelsy, as well as instrumental pieces. Pound selected from a vocal gamut of plainchant, homophony, troubadour melodies, bel canto and nineteenth century opera clichés, as well as 20th-century polyrhythms and cabaret style singing.

Pound's music theories are reactionary and revolutionary, irascible and philosophic. His reach passes through the physical science of sound to offer many epiphanies.

Importance

Because of his political views, especially his support of Mussolini and his anti-Semitism, Pound attracted much criticism throughout the second half of the twentieth century. As historical revisionist models of criticism wane, however, it seems as though Pound scholars are becoming interested in his words and not his views. It is almost impossible to ignore the vital role he played in the modernist revolution in 20th century literature in English. Pound's perceived importance has varied over the years. The location of Pound -- as opposed to other writers such as T.S. Eliot -- at the centre of the Anglo-American Modernist tradition was famously asserted by the critic Hugh Kenner, most fully in his account of the Modernist movement titled The Pound Era. The critic Marjorie Perloff has also insisted upon the centrality of Pound to numerous traditions of "experimental" poetry in the 20th century.

As a poet, Pound was one of the first to successfully employ free verse in extended compositions. His Imagist poems influenced, among others, the Objectivists. The Cantos and many of Pound's shorter poems were a touchstone for Allen Ginsberg and other Beat poets; Ginsberg made an intense study of Pound's use of parataxis which had a major influence on his poetry. Almost every 'experimental' poet in English since the early 20th century has been considered by some to be in his debt.

As critic, editor and promoter, Pound helped the careers of Yeats, Eliot, Joyce, Wyndham Lewis, Robert Frost, William Carlos Williams, H.D., Marianne Moore, Ernest Hemingway, D. H. Lawrence, Louis Zukofsky, Basil Bunting, George Oppen, Charles Olson and other modernist writers too numerous to mention as well as neglected earlier writers like Walter Savage Landor and Gavin Douglas.

Immediately before the first world war Pound became interested in art when he was associated with the Vorticists (Pound coined the word). Pound did much to publicize the movement and was instrumental in bringing it to the attention of the wider public (he was particularly important in the artistic careers of Henri Gaudier-Brzeska and Wyndham Lewis).

As translator, although his mastery of languages is open to question, Pound did much to introduce Provençal and Chinese poetry to English speaking audiences. For example, insofar as major poets such as Cavalcanti and Du Fu, are known to the English speaking world, it is mainly because of Pound. He revived interest in the Confucian classics and introduced the West to classical Japanese poetry and drama (e.g. the Noh). He also translated and championed Greek, Latin and Anglo-Saxon classics and helped keep these alive for poets at a time when classical education and knowledge of anglo-saxon was in decline.

In the early 1920s in Paris, Pound became interested in music, and was probably the first serious writer in the 20th century to praise the work of the long-neglected Italian composer Antonio Vivaldi and to promote early music generally. He also helped the early career of George Antheil, and collaborated with him on various projects.

The secret to Pound's seemingly bizarre theories and political commitments perhaps lie in his occult and mystical interests, which biographers have only recently begun to document. 'The Birth of Modernism' by Leon Surette is perhaps the best introduction to this aspect of Pound's thought.

Selected works

- 1908 A Lume Spento, poems.

- 1908 A Quinzaine for This Yule, poems.

- 1909 Personae, poems.

- 1909 Exultations, poems.

- 1910 Provenca, poems.

- 1910 The Spirit of Romance, essays.

- 1911 Canzoni, poems.

- 1912 Ripostes of Ezra Pound, poems.

- 1912 Sonnets and ballate of Guido Cavalcanti, translations.

- 1915 Cathay, poems / translations.

- 1916 Certain noble plays of Japan: from the manuscripts of Ernest Fenollosa, chosen and finished by Ezra Pound, with an introduction by William Butler Yeats.

- 1916 "Noh", or, Accomplishment: a study of the classical stage of Japan, by Ernest Fenollosa and Ezra Pound.

- 1916 The Lake Isle, poem.

- 1917 Lustra of Ezra Pound, poems.

- 1917 Twelve Dialogues of Fontenelle, translations.

- 1918 Quia Pauper Amavi, poems.

- 1918 Pavannes and Divisions, essays.

- 1919 The Fourth Canto, poems.

- 1920 Umbra, poems and translations.

- 1920 Hugh Selwyn Mauberley, poems.

- 1921 Poems, 1918-1921, poems.

- 1922 The Natural Philosophy of Love, by Rémy de Gourmont, translations.

- 1923 Indiscretions, essays.

- 1923 Le Testament, one-act opera.

- 1924 Antheil and the Treatise on Harmony, essays.

- 1925 A Draft of XVI Cantos, poems.

- 1927 Exile, poems

- 1928 A Draft of the Cantos 17-27, poems.

- 1928 Ta hio, the great learning, newly rendered into the American language, translation.

- 1930 Imaginary Letters, essays.

- 1931 How to Read, essays.

- 1933 A Draft of XXX Cantos, poems.

- 1933 ABC of Economics, essays.

- 1933 Cavalcanti, three-act opera.

- 1934 Homage to Sextus Propertius, poems.

- 1934 Eleven New Cantos: XXXI-XLI, poems.

- 1934 ABC of Reading, essays.

- 1935 Make It New, essays.

- 1936 Chinese written character as a medium for poetry, by Ernest Fenollosa, edited and with a foreword and notes by Ezra Pound.

- 1936 Jefferson and/or Mussolini, essays.

- 1937 The Fifth Decade of Cantos, poems.

- 1937 Polite Essays, essays.

- 1937 Digest of the Analects, by Confucius, translation.

- 1938 Culture, essays.

- 1939 What Is Money For?, essays.

- 1940 Cantos LII-LXXI, poems.

- 1944 L'America, Roosevelt e le Cause della Guerra Presente, essays.

- 1944 Introduzione alla Natura Economica degli S.U.A., prose.

- 1947 Confucius: the Unwobbling pivot & the Great digest, translation.

- 1948 The Pisan Cantos, poems.

- 1950 Seventy Cantos, poems.

- 1951 Confucian analects, translated by Ezra Pound.

- 1956 Section Rock-Drill, 85-95 de los Cantares, poems.

- 1956 Women of Trachis, by Sophocles, translation.

- 1959 Thrones: 96-109 de los Cantares, poems.

- 1968 Drafts and Fragments: Cantos CX-CXVII, poems.

- 1997 Ezra Pound and Music, essays.

- 2002 Canti postumi, poems

- 2003 Ego scriptor cantilenae: The Music of Ezra Pound, operas/music.

Audio recordings

- Recording of "Usura" Canto XLV, read by Pound (mp3).

- Recording of sections from Hugh Selwyn Mauberley and others, read by Pound (RealAudio).

- Ego scriptor cantilenae: The Music of Ezra Pound, excerpts from the two operas plus three works for solo violin, selected from performances all over the world.

- "The Four Steps" talk, in which Pound outlines his antipathy towards all forms of bureacracy - BBC Home Service 21 June 1958 (RealAudio).

Readings of Ezra Pound's work by other than author

- Complete recordings with full text of all 15 Cathay translations. (Public domain MP3)

- Recording with full text Two selections from Pound's Ripostes: "The Seafarer" and "The Alchemist." (Public domain MP3)