Battle of Hastings

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: British History 1500 and before (including Roman Britain)

| Battle of Hastings | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Norman Conquest | |||||||

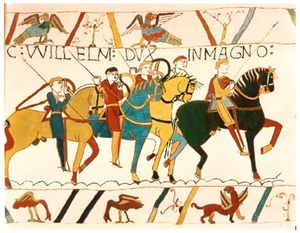

A section of the Bayeux Tapestry, chronicling the English/Norman battle in 1066 which led to the Norman Conquest. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Combatants | |||||||

| Normans, supported by Bretons, Aquitanians, Flemings & French | Anglo-Saxons | ||||||

| Commanders | |||||||

| William of Normandy, Odo of Bayeux | Harold Godwinson† | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 7,000-8,000 | 7,000-8,000 | ||||||

| Casualties | |||||||

| Unknown, thought to be around 2,000 killed and wounded | Unknown, but significantly more than the Normans | ||||||

The Battle of Hastings was the most decisive Norman victory in the Norman conquest of England. On October 14, 1066, the Normans of Duke William of Normandy (aka "Guillaume Le Conquérant" in Norman, "William the Conqueror" in English) defeated the English army led by King Harold II.

Harold had claimed the throne of England for himself in January of that year soon after Edward the Confessor died, ignoring William's earlier claims. The resulting Norman Invasion of England remains the last time England has been conquered by a foreign power.

On September 28, 1066, William of Normandy, asserting by arms his claim to the English crown, landed unopposed at Pevensey after being delayed by a storm in the English Channel. Legend has it that upon setting foot on the beach, William tripped and fell on his face. Turning potential embarrassment in front of his troops into a face-saving exercise, he rose with his hands full of sand and shouted "I now take hold of the land of England!" This bears suspicious resemblance to the story of Julius Caesar's invasion of Britain; and was probably employed by William's biographer to enhance the similarities between Caesar and William.

On hearing the news of the landing of the Duke's forces, the English Harold II, who had just destroyed an invading Norwegian army under King Harald Hardråda and Tostig Godwinson (Harold's brother) at the Battle of Stamford Bridge, hurried southward from London the morning of the 12th, gathering what forces he could on the way. He arrived at the battlefield the night of 13 October 1066.

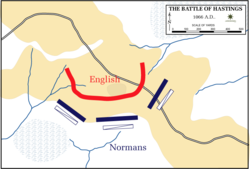

Harold deployed his force, astride the road from Hastings to London, on Senlac Hill some six miles inland from Hastings. To his back was the great forest of Anderida ( the Weald) and in front the ground fell away in a long glacis-like slope, which at the bottom rose again as the opposing slope of Telham Hill. The later town called Battle in the modern county of East Sussex was named to commemorate this event.

The English force is usually estimated at seven to eight thousand strong, and consisted entirely of infantry (the English rode to their battles but did not fight from horseback). It comprised the English men-at-arms of the fyrd, mainly thegns (the English equivalent of a land-holding aristocracy), along with a substantial amount of local peasant levies, lesser thegns, and a core of professional warriors: Housecarls, the King's royal troops and bodyguards. The thegns and housecarls, probably veterans of the recent Stamford Bridge battle, were armed principally with swords, spears, and in some cases the formidable Danish axes, and were protected by coats of chainmail and their shields. They took the front ranks, forming a ' shield wall' with interlocking shields side by side. Behind the thegns and housecarls, the lesser thegns and peasant levies were armed with whatever weapons they had at hand. The entire army took up position along the ridgeline; as casualties fell in the front lines the lesser thegns and peasants would move forward to fill the gaps. The English, however, were still exhausted from the Battle of Stamford Bridge, where they had achieved an almost- Pyrrhic victory against the Vikings, and were in no shape to fight again.

On the morning of Saturday, 14 October 1066, Duke William of Normandy gathered his army below the English position. The Norman army was of comparable size to the English force, and composed of William's Norman, Breton and Flemish vassals along with their retainers, and freebooters from as far away as Norman Italy. The nobles had been promised English lands and titles in return for their material support: the common troopers were paid with the spoils and "cash", and hoped for land when English fiefs were handed out. Many had also come because they considered it a holy crusade, due to the Pope's decision to bless the invasion. The army was deployed in the classic medieval fashion of three divisions, or "battles" - the Normans taking the centre, the Bretons on the left wing and the Franco-Flemish on right wing. Each battle comprised infantry, cavalry and archers along with crossbowmen. The archers and crossbowmen stood to the front for the start of the battle.

Legend has it that William's minstrel and knight, Ivo Taillefer, begged his master for permission to strike the first blows of the battle. Permission was granted, and Taillefer rode before the English alone, tossing his sword and lance in the air and catching them while he sang an early version of The Song of Roland. The earliest account of this tale (in The Carmen de Hastingae Proelio) says that an English champion came from the ranks, and Taillefer quickly slew him, taking his head as a trophy to show that God favoured the invaders: later 12th century sources say that Taillefer charged into the English ranks and killed one to three Englishmen before suffering death himself. Regardless, fighting was now underway.

The battle

The battle commenced with an archery barrage from the Norman archers and crossbowmen. However, the Norman archers drew their bowstrings only to the chest and their crossbows were loaded by hand without assistance from a windlass, so most shots either failed to penetrate the housecarls' shields or sailed over their heads to fall harmlessly beyond. The Normans therefore had no other choice other than to charge the English time and time again, only to be repulsed. Another tactic used was to pretend to retreat and then when the English chased after them off the hill they were fighting on, without warning the Normans would turn round and attack with the English away from cover. In any event, the archery failed to make any impression on the English lines. Norman archery tactics in general relied on picking up enemy arrows shot back at them, and as the Saxons had left their bowmen in York during the rush to meet William, the Norman arrowfire soon decreased.

The Norman infantry and cavalry then advanced, led by the Duke and his half-brothers: Bishop Odo and Count Robert of Mortain. All along the front, the men-at-arms and cavalry came to close quarters with the defenders, but the long and powerful Danish axes were formidable and after a prolonged melee the front of the English line was littered with cut down horses and the dead and dying. The shield wall remained intact, and the English shouted their defiance with "Olicrosse!" (holy cross) and "Ut, ut!" (out, out). The Normans responded with "Dex aїe!" (God's help).

However, the Bretons on the left wing (where the slope is gentlest), came into contact with the shield wall first. Seemingly unable to cope with the defence, the Bretons broke and fled. The Bretons, due to their Alannic influence, were experienced in cavalry tactics and may have set up a feigned retreat. Possibly led by one of Harold's brothers, elements of the English right wing broke ranks and pursued the Bretons down the hill in a wild unformed charge. On the flat, without a defensive shield wall formation, the English were charged by the Norman cavalry and slaughtered.

This eagerness of the English to switch to a premature offensive was noted by Norman lords and the tactic of the 'feigned' flight was used with success by the Norman horsemen throughout the day. With each subsequent assault later in the day, the Norman cavalry began a series of attacks each time, only to wheel away after a short time in contact with the English line. A group of English would rush out to pursue the apparently defeated enemy, only to be ridden-over and destroyed when the cavalry wheeled about again to force them away from the shield wall.

The Normans retired to rally and re-group, and to begin the assault again on the shield wall. The battle dragged on throughout the remainder of the day, each repeated Norman attack weakening the shield wall and leaving the ground in front littered with English and Norman dead.

Toward the end of the day, the English defensive line was depleted. The repeated Norman infantry assaults and cavalry charges had thinned out the armoured housecarls, the lines now filled by the lower-quality peasant levies. William was also worried, as nightfall would soon force his own depleted army to retire, perhaps even to the ships where they would be prey to the English fleet in the Channel. Preparing for the final assault, William ordered the archers and crossbowmen forward again. This time the archers fired high, the arrows raining upon the English rear ranks and causing heavy casualties. As the Norman infantry and cavalry closed yet again, Harold received a mortal wound. Traditionally he is believed to have been pierced through the right eye by an arrow (through interpretation of the Bayeux Tapestry). But The Carmen de Hastingae Proelio describes how Harold was cut to pieces by Norman knights led by William himself: and the Bayeux Tapestry shows him being cut down by a Norman knight, thus agreeing with The Carmen. It is possible that both versions of Harold's end are true: he was first wounded in the face by an arrow, then killed by hand weapons in the final Norman assault. Wace, in the Roman de Rou, notes that Harold was wounded in the eye, then tore out the shaft and continued to fight until cut down by a knight. Another theory was that Harold was struck in the right eye and tried to pull it out. He was later cut through the heart by a Norman knight, his head cut off, his guts strewn out, and his left leg cut off at the thigh.

The renewed Norman attack reached the top of the hill on the English extreme left and right wings. The Normans then began to roll up the English flanks along the ridgeline. The English line began to waver, and the Norman men-at-arms forced their way in, breaking the shield wall at several points. Fyrdmen and housecarls, learning that their king was dead, began streaming away from the battle; the Normans overran the hilltop in pursuit. Harold's personal guard died fighting to the last as a circle of housecarls around the king's body and his battle standards (the Dragon standard of Wessex and the Fighting man, his personal standard). Harold's corpse (through an interpretation of The Carmen) was probably emasculated by one of his attackers.

Aftermath

Only a remnant of the defenders made their way back to the forest. Some of the Norman forces pursued the English, but were ambushed and destroyed in the semi-darkness when they ran afoul of steep ground, called, in later (12th century) sources, "the Malfosse", or "bad ditch". William, after resting for a night on the hard-won ground, began the work of the Norman Conquest. He recruited his army for two weeks near Hastings, waiting for the English lords to come and submit to him. Then, after he realized his hopes of submission at that point were in vain, he began his advance on London. His army was seriously reduced for several weeks in November by dysentery, and William himself was gravely ill. Nevertheless, he directed his forces to continue their approach on the city: in three columns they made their way to Wallingford on the Thames. After crossing over, William threatened London with a siege.

After a few failed attempts at aggression near London, the fight had gone out of the remaining English nobility. The northern earls, Edwin and Morcar, Esegar the sheriff of London, and Edgar the Atheling (who had even been elected - but not crowned - "king" in a feeble attempt to continue the resistance) all came out and submitted to the Norman Duke. William was crowned as England's third king that year, on Christmas day at Westminster.

Battle Abbey was built at the site of the battle of Hastings, and a plaque marks the place where Harold fell, and where the high altar of the church once stood. The settlement of Battle, East Sussex grew up around the abbey and is now a small market town.

The Bayeux Tapestry depicts the events before and at the Battle of Hastings.

The Battle of Hastings is also an excellent example of the application of the theory of combined arms. The Norman archers, cavalry and infantry co-operated together to deny the English the initiative, and gave the homogeneous English infantry force few tactical options except defence.

However, it is quite likely that this tactical sophistication was mostly in the minds of the Norman Chroniclers. The account of the battle given in the earliest source, The Carmen de Hastingae Proelio, is one where the Norman advance surprises the English, who manage to gain the top of Senlac Hill before the Normans. The Norman Light Infantry is sent in while the English are forming their Shield Wall (to no avail) and then the main force was sent in (no distinction being made between infantry and cavalry). Interestingly, it records the first retreat of William's forces as the result of a French (not Norman) feigned retreat that went wrong, the English counter-attack, William counter-counter-attacks, and it all develops into a huge melee during which Harold is slain by a group of four knights and therefore the bulk of the English army flee.

Succeeding sources include (in chronological order) William of Poitiers' Gesta Guillelmi (written between 1071 and 1077), The Bayeux Tapestry (created between 1070 and 1077), and the much later Chronicle of Battle Abbey, the Chronicles written by William of Malmesbury, Florence of Worcester, and Eadmer’s Historia Novorum in Anglia embellishes the story further, with the final result being a William whose tactical genius was at a high level - a level that he failed to display in any other battle. Most likely is the simplest explanation: that the English were exhausted and undermanned, having lost or left behind their bowmen and many of their best housecarls on the fields of Fulford Gate and Stamford Bridge, or on the road from York. This weakness, rather than any great military genius on the part of William, led to the defeat of the Anglo-Saxons at Hastings. Even with this weakness, it was still a hard-fought battle that could easily have gone the other way.