Battle of Amiens

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Military History and War

| Battle of Amiens | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of World War I | |||||||

Amiens, the key to the west by Arthur Streeton, 1918. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Combatants | |||||||

| United Kingdom France Canada Australia United States |

German Empire | ||||||

| Commanders | |||||||

| Ferdinand Foch | Georg von der Marwitz | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 5 Aus. divisions, 4 Can. divisions, 8 British divisions, 1 American division, 12 French divisions, 1900 aircraft, 532 tanks |

25 active divisions, 4 reserve divisions, 365 aircraft |

||||||

| Casualties | |||||||

| 22,200 | 74,000 | ||||||

| Hundred Days Offensive |

|---|

| Amiens – 2nd Somme – Arras – Havrincourt – St.-Mihiel – Epéhy – Hindenburg Line – Meuse-Argonne – Courtai – Selle – 2nd Sambre |

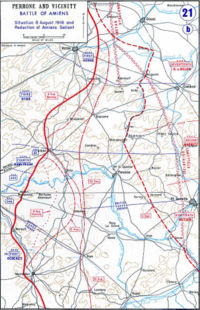

The Battle of Amiens, which began on August 8th 1918, was the opening phase of the Allied offensive later known as the Hundred Days Offensive that ultimately led to the end of World War I. Allied forces advanced over seven miles on the first day, one of the greatest advances of the war. The battle is also notable for its effects on both sides' morale and the large amount of surrendering German forces. This led Erich Ludendorff to famously describe the first day of the battle as "the black day of the German Army." Amiens was one of the first major battles involving armoured warfare and marked the end of trench warfare on the Western Front, fighting becoming mobile once again until the armistice was signed on November 11th, 1918.

Prelude

On March 21, 1918, the German Empire had launched Operation Michael, the first in a series of attacks planned to drive the Allies back along the length of the Western Front. Michael was intended to defeat the right wing of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), but lack of success before Arras ensured the ultimate failure of the offensive. A final effort was aimed at the town of Amiens, a vital railway junction, but the advance had been halted at Villers-Bretonneux by the Australians on April 4. Subsequent German offensives — Operation Georgette (April 9th–11th), Operation Blücher-Yorck (May 27), Operation Gneisenau (June 9) and Operation Marne-Rheims (July 15th—17th) — had made advances but failed to achieve a decisive breakthrough.

At the end of the Marne-Rheims offensive Allied commander Ferdinand Foch ordered a counter-offensive which led to the Second Battle of the Marne. The Germans, recognising their untenable position, withdrew from the Marne to the north. Foch now tried to move the Allies back onto offense and he agreed on a proposal by the commander of the BEF, Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig, to strike on the Somme, east of Amiens and southwest of the 1916 battlefield of the Battle of the Somme.

Plan

Foch had defeated a large amount of German forces at the Second Battle of the Marne and believed he could begin an offensive in the north of France. Foch disclosed his plan on July 23, 1918 following the German retreat that had begun July 20th. The plan called for reducing the Saint-Mihiel salient (which would later see combat in the Battle of Saint-Mihiel) and liberating the railroad lines that ran through Amiens. Foch planned the operations to start on August 8th with a combination of British, French, Australian, and Canadian divisions along with a single American division and around 580 tanks (150 in reserves as supply and repair vehicles). 1,386 guns and howitzers, making up 27 medium artillery brigades and 13 heavy batteries, were responsible for artillery cover. A key factor in Foch's plan was secrecy, there was to be no pre-battle bombardment, only the artillery fire immediately prior to the advance of Australian, Canadian, and British forces. Although the French had 72 Whippets to follow up their advance they had no heavy tanks with which to lead the main assault and so had a 45 minute preliminary barrage starting at zero hour.

Although the Germans were still on the offensive in late July 1918 the Allies were strengthening their positions. German commanders realized in early August that their forces might be forced to defend, though Amiens was not considered to be a likely front. Germans believed Foch would likely attack the aforementioned Saint-Mihiel front, either east of Reims or near Mount Kemmel; while they believed British would attack along either the Lys or Somme Rivers. German forces began to withdraw from the Lys and other fronts in response to these theories. The Allies maintained equal artillery and air fire along their various fronts, only moving troops at night, and making fake movements during the day to mask their actual intent. The German 27th Division actually attacked the Amiens front planned for the August 8th Allied offensive on August 6th, penetrating roughly 800 yards into the one-and-a-half mile front. The division moved somewhat back to its original location on the morning of the 7th, but the movement still required changes to the Allied plan. The Allies did various things to maintain the secrecy of the attack including not bringing the Canadian Corps into position from the north until August 7th, pasting the notice "Keep Your Mouth Shut" into orders issued to the men, and never using the actual word "offensive".

Battle

The battle began in dense fog at 4:20 AM on August 8th, 1918. British forces under Rawlinson were the farthest north in the battle, with Canadian and Australian forces at the centre of the field, and the French forces under Debeny in the south. Although German forces were alert on August 8th this was largely to stop potential retaliation for their August 6th incursion and not because they had learned of the pre-planned Allied attack. Although the two forces were within 500 yards of one another gas bombardment was very low as a bulk of the Allied presence was unknown to the Germans. The attack was so unexpected that German forces only began to return fire on Allied positions after five minutes, and even then at the positions forces had assembled at for the start of the battle and had long since abandoned.

In the first phase seven divisions attacked, the British 18th (Eastern) and 58th (2/1st London) divisions, the Australian 2nd and 3rd divisions, and the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Canadian divisions. These troops were to capture the first German position, advancing about 4000 yards, an objective they had reached by about 7:30 AM.

In the centre, the leading divisions had been followed up by supporting units who would move through to attack the second objective a further two miles distant. Australian units had reached their first objectives by 7:10 AM, and by 8:20 AM the Australian 4th and 5th and the Canadian 4th divisions moved off, passing through the initial hole torn in the German line. The third phase of the attack was to have been performed by infantry-carrying Mark V* tanks however the infantry were able to carry out this final step unaided. The Allies had penetrated well to the rear of the German defences and cavalry now continued the advance, one brigade in the Australian sector and two cavalry divisions in the Canadian sector. Allied forces harassed German positions throughout the advance, RAF and armored car fire kept retreating Germans from rallying.

Canadian and Australian forces in the centre, aided heavily by tanks, had quickly advanced, pushing the line 3 miles forward from its starting point by 11 AM. The speed of their advance aided in their activities, capturing a party of officers, and some divisional staff, eating breakfast. A gap 15 miles long was punched in the German line south of the Somme by the end of the day's advance. The British Fourth Army had taken 13,000 prisoners while the French had taken a further 3,000. Total German losses were estimated to be 30,000 on 8 August. The Fourth Army's casualties, British, Australian and Canadian infantry were approximately 8800, exclusive of tank and air losses and their French Allies.

German Army Chief of Staff Paul von Hindenburg noted the Allies use of surprise and that Allied destruction of German lines of communication had hampered potential German counter-attacks by isolating command positions. The German general Erich Ludendorff described the first day of Amiens as "the black day of the German Army", not because of the ground lost to the advancing Allies but because the morale of the German troops had sunk to the point where large numbers of troops began to capitulate. Allied forces had pushed, on average, seven miles into enemy territory by the end of the day. The Canadians gained 8 miles, Australians 7, British 2 and the French 5 miles.

Later fighting

The advance would continue, but without the spectacular results of August 8th. This is possibly because the rapid gains of the infantry had outrun the supporting artillery and the initial force of more than 500 tanks that played a large role in the initial Allied success On August 10th there were signs that the Germans were pulling out of the salient from Operation Michael. According to official reports the Allies had captured nearly 50,000 prisoners and 500 guns by August 27th. Even with the lessened armor the British had driven 12 miles into German positions by August 13th.

Aftermath of the Battle

The Battle of Amiens was a major turning point in the tempo of the war. The Germans had started the offensive before the war devolved into trench warfare with the Schlieffen Plan, the Race to the Sea slowed movement on the Western Front, and the German Spring Offensive earlier that year had once again given Germany the offensive edge on the Western Front. Armored support helped the Allies tear a hole through trench lines, weakening once impregnable trench positions. The British Third army with no armored support had almost no effect on the line while the Fourth with less than a thousand tanks broke deep into German territory, for example. Australian commander John Monash was knighted by King George V in the days following the battle.

British war correspondent Philip Gibbs noted Amiens' effect on the war's tempo, saying on August 27th that "the enemy...is on the defensive" and "the initiative of attack is so completely in our hands that we are able to strike him at many different places." Gibbs also credits Amiens with a shift in troop morale, saying "the change has been greater in the minds of men than in the taking of territory. On our side the army seems to be buoyed up with the enormous hope of getting on with this business quickly" and that "there is a change also in the enemy's mind. They no longer have even a dim hope of victory on this western front. All they hope for now is to defend themselves long enough to gain peace by negotiation."