[This post describes research from two papers: Interventions for Softening Can Lead to Hardening of Opinions: Evidence from a Randomized Controlled Trial, published at The Web Conference 2021, and The Effect of Spokesperson Attribution on Public Health Message Sharing During the COVID-19 Pandemic, published in PLOS ONE.]

By their very title, influencers on social media are perceived to have the power to sway public opinion. More traditionally, celebrity endorsement has been an important aspect of product and image promotion for decades. As a result, people of fame have long used their clout to raise awareness for topics they deem important (consider Beyoncé’s feminist activism or Leonardo DiCaprio’s outspokenness on Climate Change). Governments have even enlisted celebrities as spokespersons in information campaigns, including during times of crisis such as the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, to raise awareness for social distancing or support vaccination efforts.

On the other hand, the Web is not a place that is particularly known for rational arguments, the successful persuasion of strangers, or collective and rational consensus. Quite the opposite, in fact. Whether one considers political topics such as immigration, medical questions such as vaccination, scientific insights such as climate change, or even just the individual reaction to a crisis situation such as COVID-19 lockdowns, denizens of the web are divided. Polarization and tribalism run rampant, and everyone from celebrities to scientific experts on the opposite spectrum of a group’s opinion are likely to be the subject of cancelation attempts or much worse.

So, what might the outcome be when these two worlds collide? What happens to our opinions when a friendly face is put on an argument that coincides with our own beliefs, or runs against it? Might the argument become more convincing, will extreme opinions mellow? Beyond our opinion on the topic in question itself, will our relationship with the spokesperson also change? Might they become more likeable or more vilified in our eyes for their support or for disagreeing with us?

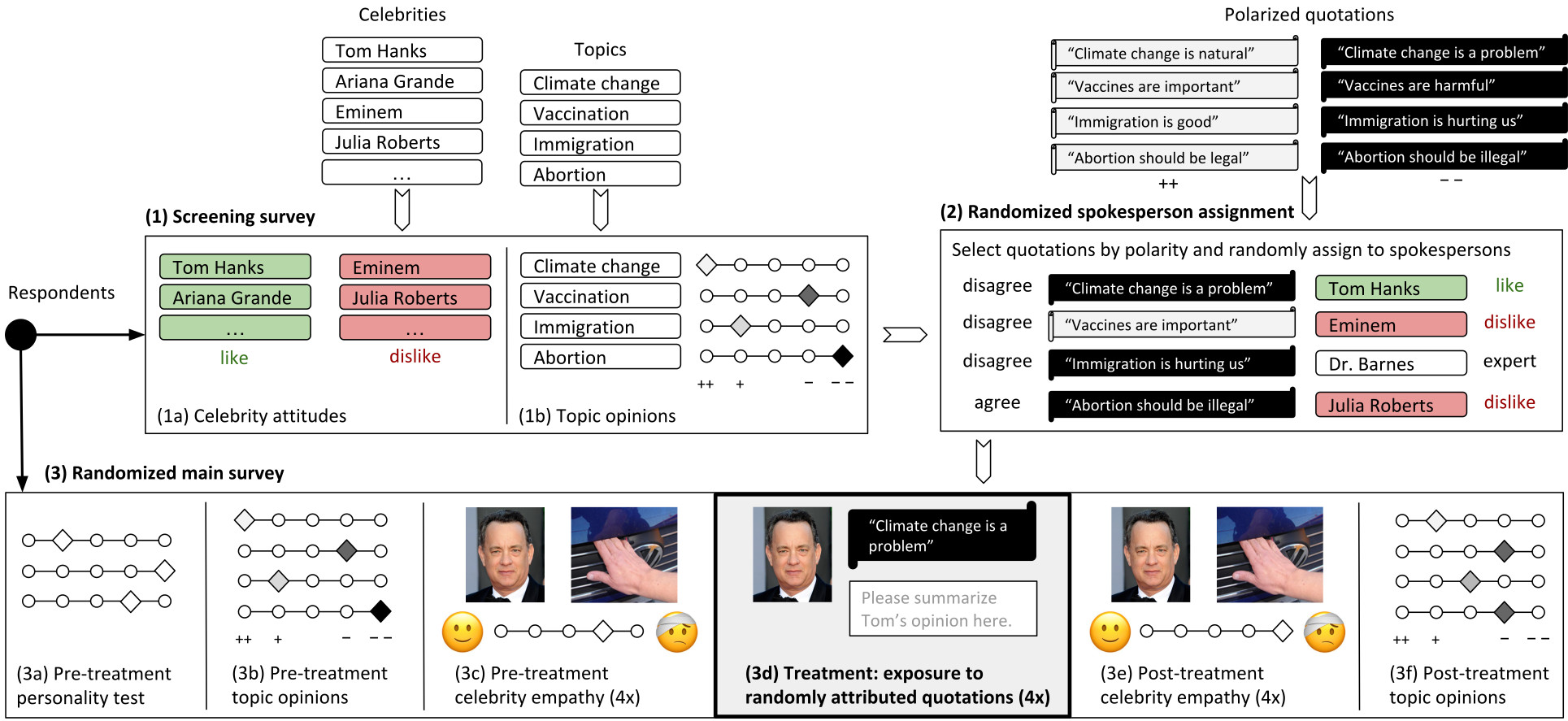

To investigate these questions experimentally, we performed a randomized controlled trial with crowdworkers. In it, we first established respondents’ opinions towards a selection of contemporary topics (immigration, vaccination, climate change, and abortion) on a scale between the two extreme opinions one could typically hold (for example, that vaccination is helpful or harmful). We also elicited respondents’ attitudes towards a number of candidate celebrity spokespersons. Using this information, we then randomly assigned respondents to experimental groups, in which we confronted them with dissenting opinions from celebrities they liked, dissenting opinions from celebrities they disliked, agreeing opinions from celebrities they disliked, or a dissenting opinion from an expert who was unknown to them.

To measure the effect of this “treatment”, we recorded respondents’ opinions on the topics before and after being subjected to the spokesperson’s opinion. We also determined the empathy of respondents towards the spokesperson before and after the treatment with an empathy-for-pain-test, in which a picture presented the spokesperson in a painful situation. (See the following figure for a schematic overview of our experimental design.)

[Overview of the experimental design. (1) Respondents’ attitudes towards celebrities and opinions on topics are elicited in a screening survey. (2) Respondents are randomly assigned one of 4 experimental conditions per topic. Spokesperson–quotation pairs that match the conditions are generated based on the screening responses. (3) The main survey establishes respondents’ personality, as well as their opinions on the 4 topics and their empathy for the 4 spokespersons in an empathy-for-pain test before and after treatment. Treatment consists of 4 separate interactions with the assigned quotations (one per topic) that are attributed to the assigned spokespersons.]

Why would I care what you think?

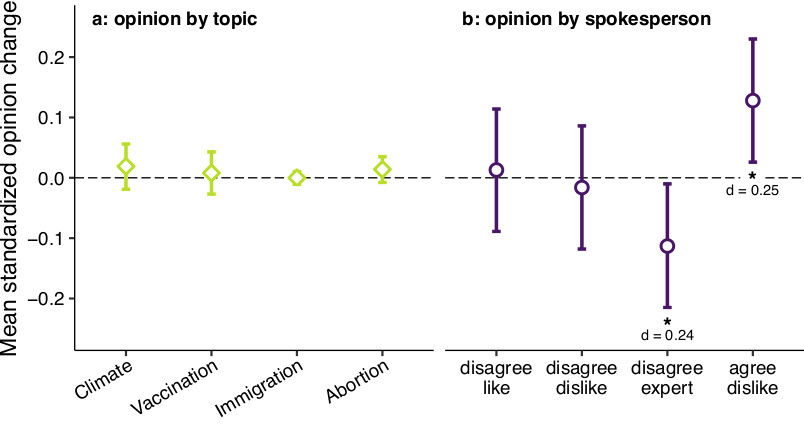

In contrast to what one might hope for from a situation in which a liked celebrity supports an unpopular opinion, changing respondents’ previously held opinions by confronting them with an opposite opinion was entirely unsuccessful in our experiment. If a celebrity spokesperson disagreed with the respondent’s prior opinion towards the topic, the attitude towards the celebrity (i.e., whether the respondent liked or disliked the celebrity) had no impact on the shift in opinion. Even more interesting, an agreeing opinion voiced by a disliked celebrity seems to have resulted in an entrenchment that caused respondents to further hold onto their prior beliefs. One possible interpretation for this observation is a justification effect, along the lines of, “How wrong could I possibly be if even this horrible person agrees with me?” Overall, our findings appear consistent with people’s tendency to surround themselves with those with whom they agree to receive validation.

One might expect this to be different when opposing opinions are supported by an expert spokesperson, not least because these opinions are based on scientific facts. But here, too, we found a similar fortification effect. Respondents became further entrenched in their own prior opinion. In contrast to dissenting celebrity opinions, which had no effect, a dissenting opinion by an expert seems to have instilled the desire to actively push back and retreat even further into firmly held beliefs. In other words, disagreement by an expert had a worse effect than disagreement by a disliked celebrity spokesperson. This clearly puts into question the perceived influence of experts and their ability to mediate in such situations. A potential explanation for this stronger reaction to the expert’s opinion is the observation that the expert, as a knowledgeable person on the topic, has a greater ability to invalidate one’s own opinion on a scientific basis and therefore has to be “shut down” in order to preserve a previously held belief.

[Mean change in opinion as a result of being confronted with the spokesperson’s opinion (a) by topic and (b) by spokesperson. Positive values denote a shift towards the treatment quotation. (Asterisks denote significance levels p < 0.05. Cohen’s d is shown for significant effects).]

I like my opinion, so I won’t like you

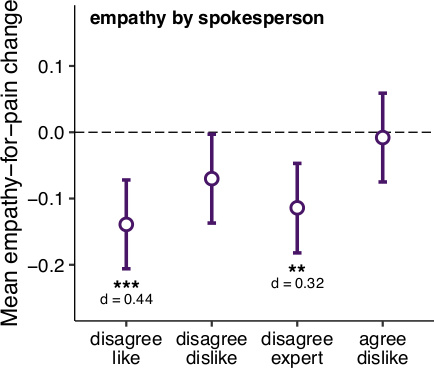

The results are even more dramatic if we also consider respondents’ emotional responses and empathy towards the spokespersons. We find that, overall, being subjected to any kind of dissenting opinions made respondents less empathic towards the spokesperson. The only group which did not exhibit this reaction were participants that were subjected to an agreeing opinion. We observed a decrease in empathy also for the expert spokesperson, which is doubly bad news. Not only does the expert completely fail in mellowing the respondent’s opinion, they also draw their ire as a result of the attempt.

[Mean change in empathy as a result of being confronted with the spokesperson’s opinion by spokesperson. Positive values denote an increase in empathy (Asterisks denote significance levels ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. Cohen’s d is shown for significant effects)]

Changes in the language that respondents used in their written opinions on the topics before and after the treatment phase indicate that this seems to be a punitive effect, in which liked spokespersons in particular were liked less as a result of disagreeing with a respondent’s opinion.

From these results, it is clear that the recommendation to not argue with strangers on the Web doesn’t go quite far enough. It seems that even the pseudo-personal rapport that regular people often have with celebrities is insufficient in changing their minds. Disagreement in any form seems unlikely to facilitate even the slightest change in opinion for the better, and often reinforces existing beliefs. Even worse, a celebrity spokesperson who attempts to change public opinion might lose followers as a result, or a regular user of the Web might lose friends on social media. When confronted with a dissenting opinion, the common reaction does not seem to be a desire to work towards a consensus, but to protect one’s own opinion. For scientific experts, our findings are a clear indication to tread carefully in communicating scientific findings about loaded and polarizing topics.

However, not all topics are discussed in a setting in which the lines are already drawn and opinions are firmly established. In situations where a common enemy, such as an adverse condition, threatens members of all tribes alike and individual interests align more closely with public interests, it stands to reason that tribalism takes a back seat to guidance and expertise. In situations of crisis, in which even an in-group consensus is yet to be found, expert opinions might fall on more fertile ground.

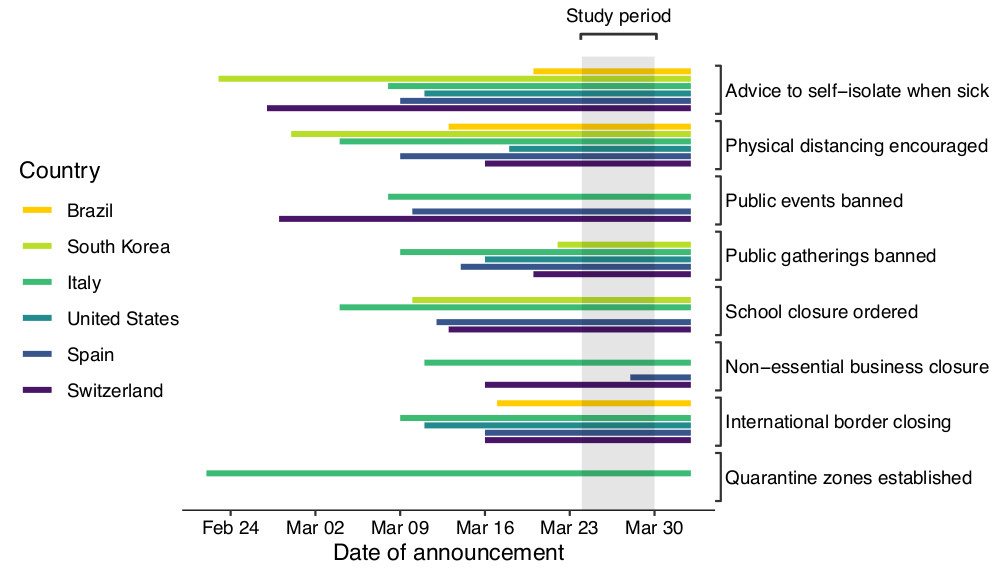

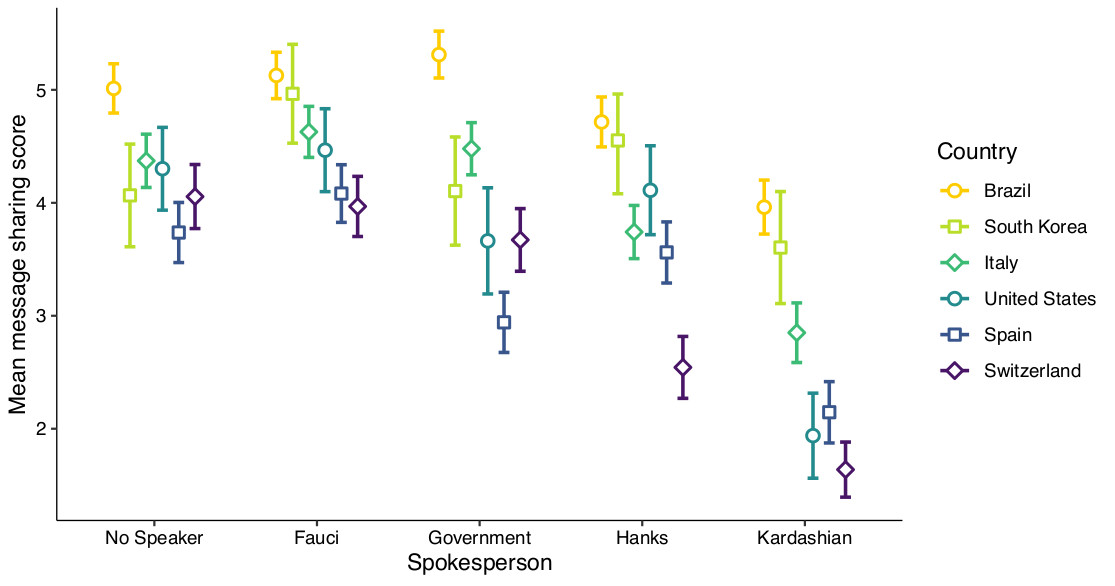

To further investigate this line of thought, we conducted a second experiment during such a crisis situation: the onset of the global COVID pandemic in the spring of 2020. At a time when most of the world’s governments were figuring out how to craft a political response, we considered the public response to social distancing recommendations in six countries that were hit heavily by the pandemic (Brazil, Italy, South Korea, Spain, Switzerland, and the United States). In a similar randomized controlled setup as our first study, we distributed calls to practice social distancing on Facebook, which we randomly attributed to a celebrity, a local government official, or the immunologist Dr. Anthony Fauci as an expert spokesperson. A control group received the message without an attributed spokesperson. To measure the impact that this attribution had, we recorded the willingness of participants to reshare the message to their social media contacts.

[Temporal context of the study. We show the dates at which key social distancing measures were announced on a national level by countries in the study. The time frame of data collection (March 24–30, 2020) is highlighted in gray. Empty bars indicate that no action was announced or taken by the national government (for comparability between federal states and unitary states, we only considered announcements by the federal government in federated countries, even though there may have been actions on a local, city, or state level).]

Is anyone here a doctor? We need an expert!

In contrast to our results in a non-crisis situation, we found the expert to be most effective in increasing the redistribution of the message across all demographic groups, whereas celebrities remained ineffective. Even in direct comparison to local government officials (who were more likely to be well-known in all countries in comparison to Dr. Fauci, a U.S. citizen), the impact of attributing the call to the expert, Dr. Fauci, compared favorably. Overall and across cultural boundaries, the expert and respected heads of government fared considerably better at convincing respondents to reshare the call for social distancing than celebrities.

[Impact of the attributed spokesperson on the stated likelihood of message resharing, split by country (error bars represent 95% confidence intervals).]

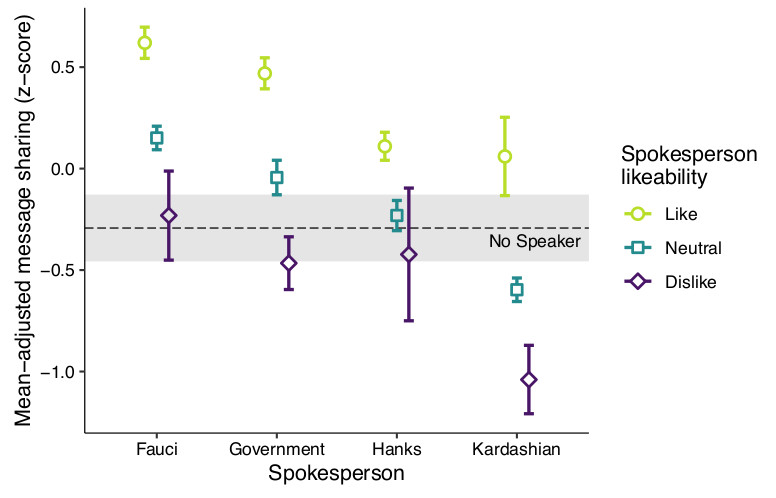

Know your audience

Our results also highlight the importance of speaking to one’s own audience, which translates to a careful selection of spokespersons for information campaigns. Across all demographic groups, respondents were more likely to heed the advice of any liked spokespersons than the advice of a disliked spokesperson or a “faceless” message without attribution. However, although this observation even holds for celebrities, the flip side of the coin shows that attributing the message to a disliked celebrity decreases the likelihood of resharing. Thus, while celebrities tend to have sway with their own audience, they should not be considered good candidates for large information campaigns that are aimed at the general public. For such campaigns, giving a stage and a voice to experts seems to be substantially more promising.

[Impact of the attributed spokesperson on the stated likelihood of message resharing, split by the respondent’s attitude towards the spokesperson (error bars represent 95% confidence intervals). The dashed black line (and the grey band as its 95% confidence interval) represents the effect of not attributing a spokesperson.]

Take home message

Addressing the public as an expert has never been easy, and our results show that the immediate effects can be harmful, unpleasant, or even counterproductive and should be approached carefully to avoid fomenting resentment and backlash. It seems important to avoid preaching from an ivory tower on issues that are polarizing, since the label “expert” seems to translate directly into a rejection of message contents that disagree with strong prior beliefs. However, there can also be no doubt about the importance of offering fact-based rationale when the situation demands it and where it is required to build consensus. Especially in times when many scientists shy away from the public spotlight, we see this as an important reminder of our responsibility. While the overall effect of spokesperson attribution to communicated information might seem small and resemble little more than a nudge, even small changes are likely to affect vast numbers of people on a societal scale in situations where a nudge is all that is needed to tip the scales.

The road ahead

In our experiments, we focused on how the cognitive dissonance of having to align the liking (or disliking) of a spokesperson with the disliking (or liking) of their opinion is resolved by respondents. Unfortunately, our findings show that the respondents’ preferred solution is to dislike the person, rather than to adapt one’s opinion. However, this dyadic interaction between two persons (the respondent and the spokesperson) and their opinions is a simplified setup, since the discussion of such topics in the real world involves substantially more participants. Future research should therefore investigate more complex situations in which two or more spokespersons are involved, what effect a mixture of opinions and attitudes towards spokespersons has, and if this could result in a more favorable resolution of the dissonance of attitudes and opinions.